Kfar Blum--Naame

Even while running this "obstacle course" I have written about, action on the hill of Naame never ceased. We developed new branches of work; we bought more tractors and equipment; and we started developing livestock branches. In the winter of 1942-1943, we sowed at Naame 450 dunams of cereals and fodder and in the Buzia fields 160 dunams of barley. We increased the area of the vegetable field and started growing potatoes. (A small fact which tells much about the situation in the country in those days -- we got the potato seed from the British Army!) The living quarters on the hill expanded and improved. At the same time, it was clear to us that we had reached the limits of expansion there, from both the economic and social points of view.

We thought it urgent that we start building our permanent housing on the spot where our permanent settlement would be. We decided to devote all our efforts to this end. Hartzfeld supported us and suggested that we get a plan for the layout of the kibbutz on its permanent site, and that we get this plan from a prominent architect, Aryeh Sharon. I hurried to Tel Aviv to see him. He was a big, tall man with an artist's head of hair, and he made a very good impression upon me. He heard what I had to say and was enthusiastic about the idea. He had been a member of Kibbutz Gan Shmuel and had experience in planning other kibbutzim. He did not ask for any payment in advance, and said he was certain that the Jewish Agency would cover the expense or give a loan for the purpose.

Sharon started to work before we had any authorization at all. He came to visit Naame. We were pleased to see how he enjoyed the scenery, and he criss-crossed the whole area, making notes. We received maps of the area from the JNF and before he started to work, he sat down with us and explained what his idea was of how a kibbutz should be planned: a country village, one-storey buildings, lots of green areas, etc. We were asked questions such as how many families we thought we would have; if we would have an industry; we spent quite a lot of time with him and we had a number of meetings.

Hartzfeld tried to help us and pressed the Jewish Agency to give us a budget for settlement. When we heard that the Jewish Agency planned on authorizing only a part of the usual budget, Hartzfeld suggested we quickly arrange a ceremony of laying the cornerstone of the kibbutz, as that might help to stimulate action. A date was set, even though the plans were not ready yet, and the spot to lay the cornerstone was chosen, just by chance, somewhere in the vicinity of the calf shed of today, not far from the banks of the Jordan.

The date chosen for the ceremony, 10.11.43 grew closer and we made our preparations. We consulted with Hartzfeld and with Chaim Gvati, a mamber of the secretariat of the Kibbutz Meuchad Movement (from our "camp") in regard to the invitation list. Most of the important guests arrived, and we also received lots of telegrams of congratulation. At the table for the important visitors sat: the representative of the Executive Committee of the Histadrut (the Labor Federation), Golda Meir.

Golda at the table for the important visitors

I and others of my age group don't recall many particulars of this event. I found a copy of the cornerstone scroll in our archives. However, there was a big write-up in the newspaper "Davar," meaning we were now on the map.

About Our Name

On the day we laid the cornerstone, we were still the Anglo-Baltic kibbutz; the event caught us in the midst of discussions about what we should call our kibbutz. I wrote about the suggestion that had come from Habonim in the States, that we should name our settlement in honor of Leon Blum. Although internally we still were arguing about what to call ourselves, the JNF in Jerusalem adopted the suggestion of the American JNF and a campaign was going on in the States to raise money. The name "Kfar Blum" was recognized outside the kibbutz as the name "de facto," but within, there were serious arguments for and against. Chaverim realized that the suggestion of the name had helped us a great deal, but nevertheless, there were objections. Chanan Shadmi wrote in "Bekibbutzenu" that he didn't think our kibbutz should be named after a politician, no matter how important, and even if he is Jewish and Zionist and President of France. Even Chanan knew that the JNF put pressure on us regarding the name, so he came up with a compromise, Nir Lavi or Maayan Lavi (Lavi in Hebrew is lion=Leon). Finally, the name Nir Lavi was chosen by a majority of the chaverim. When I talked to Chanan Shadmi about this, he said the name Nir Lavi lasted about two weeks. The JNF was adamant about the name Kfar Blum. About one year after the laying of the cornerstone, we reached an agreement with the JNF that the name should be "Kfar Blum--Naame," Naame because of our sentimental attachment to the place. This added an Israeli flavor to the name and made it more palatable to many of us.

"Kfar Blum--Naame" became the official name of the kibbutz, and that is how it appeared on the official documents. Slowly, somehow, the Naame part faded away and in time, the name Kfar Blum is what remained. The name has never caused us any problems, although we do not have any French chaverim amongst the variety of nationalities that are in our kibbutz.

While still waiting for all sorts of authorizations, and most important, for a settlement budget, we started to prepare as well as we could for the start of building. Rafael Shochat gathered a building crew and bought some machinery and wagons, and building materials. The first things we bought were with money loaned from the banks (a very poor source for investing in building). The builders also stored sand, gravel and stones. We learned from other kibbutzim that there were places along the banks of the Jordan with good sand for mixing with concrete.

The natural Jordan (not the one we know today) had many bends and these created spots that we could exploit well. Right near our building site, there was an excellent spot for swimming. This spot was used for swimming and to cross over from one side of the Jordan to the other, as there was an easy decline and incline opposite on the other shore, so that wagons could go in and out and it was a shortcut to Kibbutz Amir. We called this spot "Zhiama Beach." Sometime later, Zalman Dolev made improvements on this beach, so that is where the name comes from.

a wagon crossing the Jordan

North of Zhiama Beach, the builders found a great place with lots of sand. The Jordan took a few deep bends there and the sand just piled up there. We got the stones from a hill of basalt rock near Halsa, and we hauled the rock to the building site. Later we bought a cheap but good rock-crusher that we used to make gravel. During the war years, there was not enough cement in the country, and the British government imported it. We received a limited amount. It had to be hoarded, and the same was true for wood. Every single piece of wood was saved by the builders and used over and over again.

What with our having stored up materials and ordered the building plan early, as soon as we got the green light, we were ready to go. At the same time, lots of equipment and the sheds on the hill were transferred to the Kfar Blum site, as well as living quarters. A temporary dining hall was also erected.

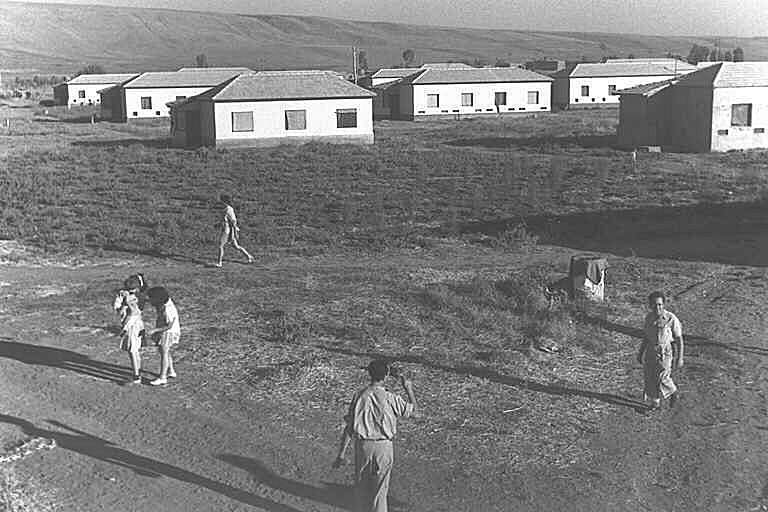

Thanks to the talent and experience of our chaver in charge of the building crew, Rafael, and the building crew itself that worked with spirit (Yoske Goral, Zev Vardi, Chaim Beitan, Shorty Cohen, Yechezkel Yahalom and Avremele Artzi), they all learned their trade while working at it, and improved as they went along. The area was surveyed by our new surveyors, Zalman Dolev and Yochanan Yokel. When they had to pour concrete, a whole bunch of us would be called in as "black laborers" to carry the pails of concrete from the machine to wherever the concrete was being poured (tough work). Soon, the concrete forms of the buildings were scattered about the landscape. That looked wonderful to us. Some of the one-storey buildings with four rooms (each room 3x4 meters, with a narrow veranda along the front of the house) can still be seen on the kibbutz. They look pretty miserable today, but they remind us, the old-timers, of those wonderful, beautiful early days, but also those very difficult ones.

the first houses of Kfar Blum -- 1945

On the parking lot of the "Gomeh" school near the play area, are some huge eucalyptus trees. They are also 50 years old or more and they, too, remind us of the old days. At the same time that we started building, we also started planting trees, and these eucalypts are the very first ones.

In the period I am now describing, of great activity in building and in moving over from the hill to our permanent spot, I had a personal incident which I recall very well. I did not deal now with affairs outside the kibbutz; I worked in farming or in temporary jobs. Beba and Dan were still in Benyamina, like all the mothers and children. Dan was already a big boy of four, and Beba was in the last month of her pregnancy.

One morning, I was assigned to transport something by wagon to Kibbutz Amir. Our contact with the outside world was through Kibbutz Amir. We would cross the Jordan at Zhiama Beach. It was a dry day after several days of rain, and the water level of the Jordan was quite high, but the experienced mules took me and the wagon across with no trouble. We reached Amir easily enough, but in the middle of the kibbutz, we got stuck in the muddy road. I got off the wagon and took the reins, shouted and pulled and encouraged the mules. They tried, but could not pull themselves and the wagon out. A chaver of Amir who came along suggested that I go to the back of the wagon and try to raise it up a little. I gave him the reins and went round to the back of the wagon and crawled under and did manage to move the wagon somewhat. It worked and the wagon moved forward. Only I was left flat on my face in the mud and with a strong pain in my back. With the help of the chaver from Amir, I mounted the wagon and made it back home and straight to bed.

Among the letters that I brought from Amir, someone told me they received news that Beba was already in the maternity ward of Beilinson Hospital. It took a few days for me to recover and get down to the hospital, and the newborn was already three days old, a beautiful baby and of normal weight. Beba was of course worried and maybe even a little angry, until she heard what had happened to me. We had chosen names for a boy or girl earlier, but on my way from Naame, I thought of the name--Yair. Beba agreed gladly, and we were both very happy. As with most chaverim of the kibbutz, we had enough reasons for wanting that we should all be united at Naame as soon as possible; but while I was lying in the mud at Amir, and Beba in the hospital, we had an additional reason.

The Kibbutz Sprouts and Grows

In the second half of 1944 and the beginning of 1945, we finally received enough land to allow for decent agricultural development. Kfar Giladi received the Jachula tract, and we received the remaining 500 dunams of Naame. We also received additional lands from the other side of the Jordan, which was given to us by the JNF. This was an important addition in quantity and in quality, as it was well drained. That allowed us to expand not only our dry farming crops, but also to plant our first fruit trees and vineyard. Finally, Michal Avin and Avramico Razili could work at their specialities; Michael had studied orchards at Kfar Giladi, and Avramico worked in the vineyard of Kvutzat Kinneret. By the end of 1944, the holes were dug in the field for planting. At the beginning of 1945, we planted "A" orchard, 15 dunams of fruit and the first vineyard, 20 dunams. Avramico told me that two chaverim of Kinneret with whom he had worked, came to take part in this planting. In 1947, we celebrated the first grape harvest, and the grapes were delicious. In 1948, we harvested our first yield of apples (3-4 tons). I missed this first grape harvest as I was in England at the time, on shlichut for the Habonim movement, and only read about the harvest. For the second harvest we were already home.

I already mentioned the "headaches" we had with some of the fields of Naame. From the gate of the kibbutz to some of our fields, we were not allowed to cross some Arab fields. We also realized that we would have to drain our fields if we wanted to get an improved yield from them. The field on the other side of the Jordan gave us a different kind of "headache." The tractors that had to cross with implements or with wagons carrying people had to go a long way along the bank to get to a bridge they could cross over. That bridge was almost on the same spot where the bridge near Naot Mordechai is today. People worked in the orchard and vineyard every day. We made a primitive ferry crossing by throwing a cable across the river and put a loop through the cable. We attached a small boat to the loop with a cord, so the boat would travel along the cable back and forth. Each day, the workers would pull themselves across in the morning and back in the evening.

Once, after a heavy rain when the waters of the Jordan were high and turbulent, the cable on the other side of the river came loose. Luckily, the boat itself was tied to a tree. We wanted to repair the damage, so it was decided that some of us swim to the other side with the loose end of the cable and tie it back. As I was a good swimmer, I and a few others, volunteered to swim across the icy-cold water and do the job.

This little ferry did its job for a number of years, but once, when I was "merakez meshek" (responsible for coordinating all the work branches of the kibbutz), I got a makeshift bridge which Zahal (the Israeli army) had discarded. Soldiers had put it together on the shore, but when they wanted to pull it across to the other side, it fell in the water, and they left it that way and went home. Our technical brain at the time was Martin Kleinman (he is the one who built the unit for drying alfalfa, the cold storage house with controlled air, etc.). With the help of a tractor and a few chaverim, Martin got the "bridge" across the river and placed it in proper position.

The area of the orchard and vineyard expanded and needed more workers. The vegetable garden also grew on that side of the river. The bridge stood us in good stead for many years, until the dam was built on the Jordan. That solved the problem of crossing, but spoiled the original Jordan River as we knew it. Even after the dam, the bridge was used for a few more years until it was considered unsafe for further use.

The Upper Galilee area had an organization called Vaad Hagush (committee of the region); this Vaad dealt with all sorts of problems or relations between the kibbutzim of the area. The Vaad started to function during the war years and would meet in one kibbutz or another. Hillel Landesman of Ayelet Hashachar and Nachum Hurwitz of Kfar Giladi were the moving personalities in the Vaad. They dealt with problems such as the relations with the English authorities in the region, security issues, and later with various economic issues, such as creating a trucking cooperative for the region and having a central storehouse for hard-to-get items, etc. Later on, this Vaad developed into what is now the Moatza Azorit (Regional Council of the Upper Galilee). Later on, after the war, Natan Cohen, from our kibbutz, became active in the Moatza Azorit. There was a split in the Vaad on the question of where to build the pasturizing plant that Tnuva intended to erect in the Galil. Representatives from Dan, Dafna, Kfar Szold, Shaar Yashuv, Bet Hillel, Huliot and Kfar Blum-Naame were for building the plant at Bet Hillel. Kfar Giladi, Ayelet Hashachar and Hulata were for building it at Jachula. Tnunva (the milk company that was built up by the kibbutz movement), decided in the end to build at Bet Hillel.

Before the whole kibbutz came up to Naame, we had already started enlarging the cow herd. Good calves were bought and the herd grew from year to year, under the baton of Eliezer Yisraeli. I recall one incident about this milk plant at Bet Hillel. I don't remember when we started hauling milk there, but anyhow, sometimes, on rainy days, we couldn't get the milk by dirt road to Bet Hillel. We hauled the milk in cans on a wagon pulled by a tractor to Kiryat Shmoneh, and from there via the Dafna road to the entrance to Bet Hillel. I did these deliveries several times. There is a dangerous place on this road where it dips into a Wadi. Going down this Wadi one rainy day, the pin that connected the wagon to the tractor jumped out, and the wagon ran into the side of the road. Only by a miracle, the milk did not spill, but I waited a long time until a truck came along and the driver helped me hitch the wagon to the tractor. Rain fell continuously, and I arrived back home soaked, dirty and exhausted.

When we were still in Naame, we thought it logical to develop fish ponds as an anaf. In 1944, we detailed the talented Moshe Niv to do this. Moshe received the permission of the Jewish Agency, and was encouraged by the experts in this field with whom he consulted. They also helped choose a good site, which was adjacent to Shwartz's fish ponds. When it came to the planning of the ponds, we ran into a bunch of technical problems that were not easy to solve. It turned out that it was difficult to supply water to the ponds; and it was difficult to arrange to drain the water when we needed to take the fish out of the ponds in order to ship them to market.

Finding solutions to the problems and the final planning took a long time, and only in the summer of 1945 was Moshe able to start digging the first ponds. Full of energy and willpower, Moshe hired five tractors for the digging and two of our own as well. Moshe found answers to the problems as they arose in the course of the work, and by the end of September, water flowed into the first pond. One after the other, the ponds were completed; water entered, and then the carp fry (newly hatched fish) were put in. Yochanan Hekler from the Youth Aliya group, joined Moshe in the fish crew. They both worked from morning to night, and when necessary, got others to help them. By the spring of 1946, the first quantities of carp were shipped to market. The yield was 200 kilograms of carp per dunam. These first ponds were rather primitive in comparison to what we have today.

During the shipping season, many chaverim would join Moshe and Yochanan in the fish ponds. They would be deep in the icy water, moving long nets to gather the fish into a smaller area and then pour the fish from pails into a container on a truck. There was a cylinder of oxygen which supplied the tank of fish so that they would arrive at market in Tel Aviv or Haifa in good condition. During the growth period of the fish, they would be fed by spreading the food by hand from small boats that circled the pond.

As this anaf grew, more chaverim entered as steady workers. Moshe became expert in this field and was appointed the adviser for the Upper Galilee, of the fish-breeding organization. After the war, a younger generation of growers entered the anaf and took it over. These were: Shmuel Halperin, Zev Shatz (Volia), Yehoshua V., Milty Shwartz and others. The ponds were improved and new equipment was bought that made the work easier. Fish breeding became an important branch of work in the kibbutz. Some of the workers continued to work for many years. Volia, who had been in charge for a number of years, passed the command to someone younger, and continued on for many more years, as long as his strength allowed him.

An End to Dispersion, We Are All HOME

As the agricultural branches grew and developed, we had to develop along with them a machine shop and a garage. Eliezer Porat, who built the machine shop, had studied that trade in a technical school in Riga. I knew Eliezer well at that time, because we lived together in a rented room. At Benyamina, Eliezer had also worked at this trade, so when he got to Naame in 1942, he was in charge of repairing all the equipment we had. In an article which he later wrote, Eliezer remarked on how, when he arrived on the hill, he was shocked by the state of the equipment, and most of the repairs had been done with wire. He started work there with the simplest tools; he didn't have a welding machine, nor an electric drill, nor an electric saw. Eliezer made some minimal improvements, but when we moved over to our permanent spot, he bought all that was vital for a machine shop and he was able to do a great variety of repair work. In time, that anaf also grew, and others joined Eliezer there. That same story goes also for Hillel Avni and the garage, and he repaired all our tractors and equipment and pumps and generator.

The second half of 1944 was a period of intensive expansion and we needed many workers in order to prepare for transferring everyone from Benyamina and Givat Naame to our permanent site. We completed 9-10 buildings, but that still was not enough for everyone, so we moved some shacks from the hill to our permanent site. Malaria would still claim a few victims now and again. Meanwhile, living conditions were also crowded in our new home.

Aside from the buildings, we still had to build showers (during that period of building, most homes did not have shower facilities; these were in a central location, one for women and one for men); we needed buildings for a laundry, for shoe repair, for a clothes store and a clinic. We had to put up a big temporary building for the dining hall, and a carpentry shop big enough to absorb our clothespin factory. This factory was working quite well, mostly for the local market, but also exported to Syria, Iraq and Jordan. By the spring of 1945, the clothespin factory was working well in Kfar Blum under its new name, "Hadek" (to secure, fasten).

The transfer from Benyamina took place during all of 1944, and was completed in January, 1945. The crowning moment of the transition was when the children were brought up to the kibbutz, in November of 1944. The month of November was a notable month in our history: in November, 1938, we had arrived in Benyamina and started on our career as a kibbutz; in November of 1943, we had laid the cornerstone of our permanent site. Now we heard the voices of our children in our own kibbutz for the first time. I remember how I tossed 4-year-old Dan high into the air, and how, with the trepidation of an inexperienced father, I held little 9-month-old Yair. This was a great day not only for the mothers and fathers, but for everyone. The parting from Benyamina and the coming to Kfar Blum was well-described by Ruth Kreydon in her letter to Yosef, who was serving in the British Army. Here is part of that letter: ".. it was surprising how many of the chaverim stood there with tears in their eyes. All the neighbors, the people of Benyamina, came to say goodbye, with presents in their hands: eggs, citrus fruit, lots of flowers and candies. The moshava doctor came and took pictures, and hugged each and every one of us. When the bus left, every inhabitant of Benyamina stood there waving goodbye--and crying! Our children were excited by the adventure! We the adults sat silently, somewhat sadly--it was an unforgettable moment.

We left at 7 AM and arrived at 1 PM. An easy and beautiful ride. When we reached Tiberias, Yamima and Rasia came to meet us. Both of them are waiting to give birth but their infants were lazy and didn't want to come out yet. It was nice to meet them. In Tiberias we transferred to another bus which took us to the bridge (the bridge near Huliot-Amir). We came early and the chaverim hadn't expected us yet, but they saw the bus coming from afar. It was a nice day and it wasn't muddy. We started to walk through the fields along the banks of the Jordan, and then a tractor and wagon came to take the children. What a beautiful picture, I photographed it, the new tractor was a bright red. Hillel was the tractorist. The tractor was decorated with flowers, and the wagon also. It was a glorious occasion and everybody cried and everybody kissed and hugged everybody else. The children filled the wagon and reached the kibbutz while the others came by foot, it wasn't far to go, and when the tractor arrived at the gates, chaverim appeared from all directions. It was a feeling which a person can have maybe once in a lifetime, if I could only picture it for you, but that's impossible. It was as if we found our lost soul! Everyone seemed to you at that moment to be your closest friend--it was beautiful and heart-warming and very joyous..."

We put a lot of effort into getting the children to Kfar Blum before winter and that, despite the rain and mud which could very well make things more difficult to settle them in properly. We wanted to make all the preparations possible until the next malaria season; enclosing the porches with netting, and keeping the children indoors after sundown. To the best of my recollection, these steps were successful.

The macheneh (camp; that is what the built-up area of the kibbutz was called) to which we brought the children was still undeveloped and lacking several important buildings necessary to a developed yishuv (settlement). There were some buildings and shacks for chaverim, two children's houses, temporary shacks for showers; laundry and clothes stores. On the north side and the south side, were two little shacks that served as outhouses, and they stood far from the dining hall and from the permanent houses (they were of a primitive nature). There were no cement paths though we knew there would be plenty of mud, and as yet no trees or bushes for landscaping. The older children participated in the first tree-planting a few months later, when we finally received the landscaping plans. Next to the house where Beba and I lived, I planted an oak tree with my son Dan.

Thirty-two children arrived at Naame that day in November, and by the end of the year, there were thirty-nine children (seven were born in November and December of that year). One children's house was for the kindergarten children and the pre-kindergarten class (in kibbutz, all the classes are given names, not numbers; later, the kindergarten class became "Snonit" {swallow} and "Dror" {sparrow}, the pre-kindergarten class was "Shaked" {almond tree}). The second house was for the infants and weaned children. The teacher of the first kindergarten was Leah Barzilai, who had studied at the Teachers' Seminary when we were at Benyamina. Before her aliya, she had studied at a seminary in Riga. The second ganenet (kindergarten teacher) was Shulamit Degani, who had joined the Anglo-Baltic group after finishing her studies at the seminary. The infants and toddlers were in the care of Edith Razili and Dvora Dolev, both of them had completed a course on infant care in the Hadassah Hospital. Other mataplot (child caretakers) had gained their experience while raising our children in Benyamina. Chanan Shadmi, or prospective teacher, had finished his studies at the Kibbitz Seminary in 1943 and was ready for the start of our school in the fall of 1945.

Upon their arrival at Naame, the children quickly became an important element in the life of the kibbutz. The children have always been considered the most impoortant possession of the kibbutz, and they were a factor that enriched our social and cultural life. I recall today Kabalat Shabbat (welcoming the Sabbath) in the children's houses; I recall the grace as well as the content that this added to our cultural activities and holidays. Most of the chaverim followed with interest all the developments concerning the children.

In the fall of 1945, we opened our school (class of Snonit). The World War was over and the whole Yishuv knew now what a terrible holocaust had befallen our nation. I viewed the opening of our tiny school as a symbol of the obstinate struggle of our nation to survive and build the future. I spoke about this at our general assembly and wrote it in our newspaper. The school opening marks a beautiful end to the first chapter in the history of our kibbutz.

The road that we had traveled together as chaverim of a young kibbutz fortified our self-confidence as partners in the building of the homeland of our nation. We saw that the kibbutz movement, to which we belonged, was a leading factor in settlement, in defense, in immigration, and in contact with the Diaspora. Those that had come before us had built the means for defense; they built the Histadrut, the Hagana, and the Palmach. I saw flaws and weak points in the kibbutz society, as no doubt others saw also; but, without a doubt, only because of the social framework of the kibbutz, was it able to succeed in carrying out its mission, without which, the Zionist ideal would not have been achieved. We made aliya because of those ideals. We lived the life of the Yishuv in Israel from the day we came to Benyamina. We fought the fight of the whole Yishuv to ensure our future in Israel; our chaverim volunteered for the Hagana and the British Army which fought against Hitler; and we maintained strong contact with the youth movement in the Diaspora, in which we ourselves had grown before making aliya. We fought against the British policy in Israel which endangered our future in Israel. Even from our little corner in the north of the country, we kept fully abreast of everything that was happening around us, and we had our own "political commentator," Rafael Bash, who was in close contact with our political party and with the Histadrut.

This feeling of doing and participating were "the spice of life" to us, strengthened us and enabled us to overcome many difficulties and disappointments. Despite all our hardships, who, of all my friends, does not recall our singing together and dancing til the small hours of the night? Our children also added to our joy of life and helped us overcome the hardships.

Kfar Blum--Naame, a kibbutz on the banks of the Jordan