Givat Naame Leads its own Life

Benyamina had the foothills of the Carmel, fields and vineyards, a great background for the flowering of romantic relations and development of new couples among the Anglo-Baltic kibbutzniks. All that was in Benyamina, but soon enough one could see that Givat Naame had its own charm. Despite the malaria in the summer and the crowded quarters, young people found each other, in the green fields, on the banks of the fish ponds or by the Jordan River. Usually, couples were of the same background, country, or youth movement, but here and there, one could also find the first hybrids, mixed couples. Each couple has its own story.

The most romantic story is that of Elah and Yoske Goral. He, from Kfar Giladi, a handsome sabra, real macho, the epitome of the Shomer in all the photos, but also a diligent worker with a good pair of hands. She, an immigrant from Dvinsk, Latvia. She was a product of the youth movement and a thorough "Puritan," strong on culture and a music lover. "It was love at first sight," Elah told me, when we had a talk on the hill. It is difficult to imagine a more romantic setting for two than Yoske's leanto on stilts, gazing over the valley. What beautiful scenery from Yoske's leanto! Of course, we joked about the two, sitting up above us and reading literature and the Bible, and listening to classical music on old records over a croaking gramophone which Yoske brought from Kfar Giladi. We made jokes about them, but in good spirit and a lot of empathy.

In time, it turned out that Yoske was in love with Elah and with Naame. It seems he even got used to the crazy Anglo-Baltic gang. The romance went on for a long time before they married. So Kfar Giladi had a double loss; the old kibbutz had to give up the land it had coveted at Naame and they lost Yoske, who joined us. He was among the first in the group that worked in building our first permanent houses. In Kfar Blum he worked at fixing the agricultural equipment, and later he was the kibbutz gardener. He also built the sports area and the swimming pool of the kibbutz. He was the one who did a beautiful landscaping job around the elementary school area.

We did not succeed in organizing cultural activities on the hill. Everything that happened in that field, happened spontaneously. Some time later, someone in Tel Aviv arranged to send us lecturers or performers from Tel Aviv to the new settlements, way up north. Sometimes, even our hill received a good lecturer or performer, and I will recount one episode that I remember. I received notice by Morse that on the following evening, the singer Rivka Machat would appear at Naame. We were asked to meet her in Halsa. Yerachmiel Sondak took upon himself to carry out that task. Yerachmiel rode on horseback to Halsa and took a mule with him for the guest. They reached the hill very late, and they both seemed very tired. We took the singer to one of the wooden shacks so that she would be able to rest. The poor soul, who was not used to riding, much less on a mule on a terrible road, could hardly walk, and was led to her room leaning on the shoulder of the girl that accompanied her.

Yerachmiel told us what had happened on the ride home. He found the visitor waiting for him in Halsa, and helped her to mount the mule. He took her suitcase from the fellow who had brought her and carried it all the way. At first, all went well, but once they left Halsa and the trail worsened and there were big puddles of water, the mule balked and he had to dismount and lead and coax the mule across the bad stretches. More than once, Yerachmiel was afraid the singer would fall off; but finally they arrived, and Yerachmiel was very relieved.

We decided to delay the performance until she could regain her composure, and to our relief and joy, she awoke after her rest feeling well and in a good mood. She asked that we wait a bit longer until she dress for her performance, but we said she looked good enough the way she was and would also enjoy her singing as she was. Rivka refused adamantly, "You are an important audience for me," she said, "and I will appear for you the way I appear to an audience in Tel Aviv." At midnight she appeared before an audience of 25 young people, tired after a day's work, but enjoying her performance thoroughly.

We did not celebrate the holidays the way we knew how to do so in Benyamina, but we did make a special effort to do the Seder Pesach as it should be done. We tried our very best to make it good. When the third group of Aliyat Noar joined us, we also received a choir leader. Chaim Probst (of blessed memory) saw to it that there were rehearsals of the small choir, and at the Seder itself, everyone joined in in the singing. The matzot, the wine and some of the special food, they sent up to us by truck from Benyamina.

One Seder Pesach was particularly dramatic. We stood waiting for the truck, which was supposed to bring a number of chaverim from Benyamina. Beba was also supposed to come, so we both remember this Seder well. The truck got stuck in the mud near the village of Naame. The chaverim were tired after the ride from Benyamina and walked to the hill from the village, and the products were loaded onto a wagon brought up by a tractor and towed to the hill. The truck stayed in the mud (with someone on guard) until the following morning. A tractor then came to pull it out. The following day was the Seder and it went off very nicely and the mood of the chevra was excellent. The importance of the holiday in its national significance was even more so than usual, under the circumstances of celebration on the hill.

Our Arab Neighbors

I came to Palestine at the time of bloody riots, when the contact between Jews and Arabs was almost nil. So long as the riots continued, I only saw Arabs at a distance. If I traveled from Afikim to Haifa, via Nazareth, Arabs passed by on both sides of the streets as we drove by. There were also Arabs at the entrance and exits of Haifa. All we heard about Arabs was riots and danger which lurk in store for travelers from the Jordan Valley to Haifa. In Afikim, I attended the funeral of a member of the kibbutz, Benny Kirshon, with whom I had worked in mispoh (fodder for cattle). He was shot and killed while riding on a truck which he was guarding.

We first met Arabs in Benyamina only after the riots stopped and the Arabs from the surrounding villages started appearing in the orchards and vineyards of the moshava. We had two "incidents." One, when our guard killed a donkey one night, and a mob of angry villagers threatened him. To the guard's luck, that incident was solved peacefully. The second time, when we tried to prevent the farmers of Zichron from bringing Arab workers to their vineyards, the Arabs sat on the sidelines and watched, tensely but peacefully.

Some time later, when I went to visit Natan in Metula, I met Lebanese Arabs who wandered about the moshava. In the Hotel "Snow of Lebanon," the owner employed two Arab boys, Musa and Ali. These two nice kids worked very hard for Brenner. The first Arab I met in the Huleh Valley was this guard Hamadi from Naame, who worked for the JNF. I once went with Moshe Nir to Hamadi's house where we were invited to a meal. There was chicken meat on a big tray of rice, round which we sat. I watched Moshe take the chicken meat in his hand wrapped in the hot rice and eat with the fingers. We drank coffee and talked while Hamadi's two older sons drove off all the little curious children who peeked through the openings.

The Arabs of Naame and the Arabs of the Huleh in general were rather dark-skinned. They were of the tribe of Ayurni, meaning "strangers." The life of the Huleh Arabs was not an easy one. They were farmers--serfs and owners of water buffalos. A serf working the land had to turn over most of the yield to the "collectors" who worked for the owners of the land. The water buffalo, "Jamus" in Arabic, pulled the plow that tilled the land, and gave milk, also. It was only a small amount of milk, but high in fat. Their turds were gathered, dried and used to make fire for cooking and baking. There was also a special industry suitable to the Huleh, weaving mats from reeds. The mats covered the floors of their little hovels, and the walls and roofs of leantos and sheds. In summer the Arabs suffered from malaria, and in winter, from the rain and cold. The children wandered half naked in summer between the hovels and ditches and puddles of water.

At first, the contact with the Arabs of Naame was very limited. Although we did go through the village very often, we rarely stopped, yet we did not feel that there was antagonism on their part. We would greet the men as we passed them by, and they returned the greeting, and that was it. Only the dogs bothered us sometimes, but they were cowards and a shout was enough to scare them off. Sometimes the curious children would follow us to the end of the village. By the way, most of the children had curly black hair, but here and there would be a redhead amongst them. Someone raised the question: Could it be that some British policeman was the father of the red-headed children?

Our relations with the Arabs of Naame and other Arabs in the Huleh started to get complicated when the areas we cultivated grew. Sometimes their buffalos would enter our fields and trample the crop. We set up a small corral on the hill, and if buffalos entered our fields, we would lead them into our corral and hold them. When the owner came to get the buffalo we would exact a small fine. This helped a bit, but not much, and once we corraled a rather large herd. Soon, a mob of Arabs came to release the herd. In the fight that followed, Eli Presser received a blow on the head from an Arab he was fighting. The episode came to an end when one chaver brought a rifle and fired a shot into the air. When Shaul, who hadn't been there the day of the fight, returned, he met with the mukhtar of Naame and the tension evaporated.

Although we were surrounded by Arab villages, we did not feel threatened. Sometimes, if we rode out to a distant field, we would take a pistol. We did not hide the weapons from the British police, as Yehuda Strimling would "take care" of them when they visited the hill. When we started to cultivate fields that were separate from the others, we encountered some uncomfortable situations. Sometimes an Arab would object to our crossing over his narrow strip to get to our field on the other side, or cross over his irrigation ditch. Also there was a permanent problem of small-scale thievery. Actually, we had no real problems with the Arabs until the years preceding the War of Independence.

We also met the Arabs of the villages on the Lebanese border. We met them in Halsa. They would come on market day or if they wanted to take the bus and ride south. These Arabs, who were called "Metualim," were Shiite Moslems, pale-skinned and had a higher standard of knowledge and economics than the Ayurni. The living standard of the Lebanese villages was higher, on the whole, than that of the Huleh Arabs. On market days there would be quite a few Metualim in Halsa, and they did not hide their feelings of superiority over the Ayurni. Once, I rode in an Arab bus with several Arabs from the village of Hunin (a large village not far from Menara today). The bus was almost empty but some Arabs stood in the entrance, so the bus didn't move. The driver honked his horn but nobody hurried and only when he started to move did they clear the doorway. However, someone yelled out for the bus to stop, and it did. I asked my neighbor, "Shu hada?" and he pointed out the window and I could see a bunch of Arabs coming from the direction of Kfar Giladi. The driver was more than willing to stop and take on more passengers, that was a common occurrence. We waited for them all to get on. It turned out that my neighbor knew Moshe Aliuwitz, one of the old Guards of Kfar Giladi, who was a good friend of the mukhtar of Hunin.

I met quite a few Arabs in my travels to and from Benyamina. I usually went by way of Haifa and Sefad. Once, when I arrived in Safed, I realized I had missed the bus to Rosh Pina. Luckily, some Arab who had also missed the bus led me to Rosh Pina by a path which was much shorter than the meandering road. I arrived so late that I had to stay for the night--in a guest room above Gitel's little restaurant. Everyone in the Galil knew Gitel's restaurant, and she knew everyone in the Galil. Who hadn't had a meal at Gitel's? Gitel charged according to how the client was dressed and how he looked. Sometimes I would patronize the Arab cafe in Halsa, opposite of where RASCO is today. This cafe also was a sort of bus station. My Arabic was not good enough for a long conversation, but I could exchange a number of words and greetings.

One particular Arab whom we got to know better than most was a Metuali named Musa who sold us meat. Musa would come riding on a mule, accompanied by his little son, Ali, who rode on a donkey. They would bring meat to sell to us and to other kibbutzim in the area. Musa and the "economit" (the one in charge of the kitchen) Musia, used to argue all the time, because she thought he was cheating her on the weight. They would also argue about payment. The treasurer would leave Musia a monthly sum for all her purchases and this was not always enough, so sometimes Musa would get an IOU on a piece of paper, where she wrote the amount of kilograms she owed him for. Other kibbutzim also used this system and Musa managed with it.

The years passed and the War of Independence drove the Arabs of the Huleh away and closed the border to the Lebanese Arabs. One night, when I was on guard duty and making my rounds, I heard whispering in Arabic. To my astonishment, I found Musa, who had infiltrated and come to collect his debt. I knew there were soldiers nearby and feared that Musa would be caught. I knew the word "soldiers" in Arabic, and "run." Musa turned and ran.

Years later, the GOOD FENCE was opened on the border of Lebanon, and the Arabs of South Lebanon would come to the Galil. One day, an Arab of about thirty-years-old appeared in the kibbutz and said he was looking for the mukhtar. Somebody understand that he meant Shaul. This Arab told Shaul that he was Ali, the son of Musa, who had already passed away. Ali pulled a bunch of IOU's out of his pocket and asked that he receive what was owed Musa for the meat he had delivered. When Shaul said it would be difficult to figure out how much the notes would be worth in the currency of the day, Ali said very simply, "Nothing to figure out; just give me the same amount of meat." I am not positive how the matter ended, but I do know that we and our neighbors in Kibbutz Amir did honor the notes and reach a decent agreement.

Stubborn, and See Light at the End of the Tunnel

Slowly but surely, the matter of land for Naame started to straighten itself out. At the end of 1941, we signed a lease for 280 dunams bordering the Jordan. I am at this moment holding in my hand a copy of this contract signed by Nachmani and myself. I found it in the archives of Kfar Blum and I was very excited to find it. This piece of land, which was leased at first for only a short period, became at a later date the keystone in our plans for settlement. It was recognized by the settlement institutions as suitable for erecting a permanent settlement.

This land was slightly higher than the surrounding area of Naame and was better drained. In the spring of 1942, we could start expanding our agriculture. It seemed most natural to start with extensive field crops not needing irrigation, but it was also important to develop our vegetable garden, which would supply work for a number of the women. We chose this new plot as suitable for the vegetable field because it was drained better, and could be easily irrigated by pumping water from the Jordan. On that point on the shore, where the tennis courts are located today, we chose to set up the pump. Hillel Avni, our tractorist and mechanic, found some old metal platform on which we placed the still-older pump. We still did not lay pipes in the field for irrigation, but this old contraption could be moved along the shore. This pile of what looked like junk served us very well.

Shmuel Paltiel was our chief gardner. He learned the trade in older kibbutzim. Two women worked with him and were the "second in command": Rivka Dukarevitch and Chaya Stern who obtained their experience in Meshek Poalot before they joined us. The vegetable garden added important items to our meagre fare. The surplus was sold, sometimes in Halsa.

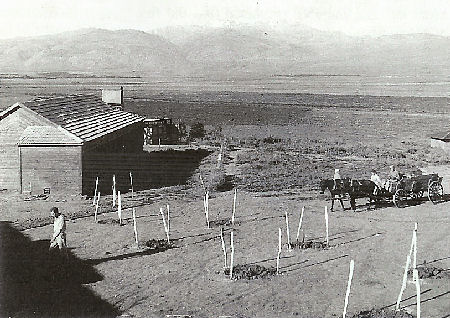

Our chief dry farming crop specialist was Moshe Nir. He went through an important period of retraining. Moshe was expert at working with horses and mules, only Monia Wilensky could match him in this area. In Naame he had to learn to work with tractors. There is a story that made the rounds by us, that his reflexes as a wagoneer helped him as a tractorist. One day, Moshe found the tractor only a few meters from the banks of the Jordan, and there was danger it would fall in. Being much more experienced with horses than with tractors, Moshe's reflexive action was to yell what one commonly yelled at horses, "Hoysa, Hoysa!" and, with that cry, Moshe pulled on both brakes with his hands, as if they were reins. The tractor came to a halt on the verge of the bank. I'm not positive if that is what really happened, or if one of our pranksters didn't invent it. This story had no bearing on Moshe's authority as head of this branch of work. Most of his crew was made up of kids from the Aliyat Noar group. Little by little, we bought implements for this anaf (branch, in Hebrew, for this branch of work). We bought plows, disks, mowers, rakers and a straw-baler, etc.; all these implements were spread over the kibbutz area, near the stable and the cowsheds and gave us the appearance of a real farm.

In our development of agricultural branches in Naame, we also made mistakes and had failures. Our first big mistake was when we bought our herd of sheep from Benyamina to Naame. Yisrulik Vishkin had worked with sheep from the time we were in Afikim. (The head of that anaf in Afikim was Lior Roth, who later became an important artist in Israel.) When we came to Benyamina, we sent Yisrulik to an older kibbutz for training in sheep-raising. When he returned to Benyamina, we bought a herd of sheep and goats which was very successful. Pasture in and around Benyamina was very good. With the growth of the herd, we developed weaving the sheep wool as another anaf. The girls washed and dyed the coarse wool and Batya Bash learned to spin yarn, from which the girls made socks and sweaters for the children

Once we received a larger plot of land, we decided to transfer the herd to Naame. We built a shed for the herd, and the beginning looked promising. Once the rainy season started, it became obvious that there was no place for a herd at Naame. Yisrulik did the best he could. When it rained, he would put a big sack over his head (nobody dreamed of raincoats), and go out to save a sheep that was drowning in the muddy soil. We sold the herd as soon as we could; took the shed apart; and later used the wood to build the cowshed.

Eliezer Yisraeli, our dairyman who had trained in Kfar Giladi, started to build the anaf refet (dairy cow herd). We had a strong work force, in quantity and quality at Naame. The young group of Aliyat Noar that had had three years' experience at Afikim were an important addition. One after another, they found their permanent niche in the various work branches. Eli Presser was sent to a signaling course and became our signalman, together with Tmima, the young American girl. The young Oleh from the USA, Yehuda Strimling, was our contact man with the British police. Shaul remained the mukhtar for contact with the Arabs. Rafael Shochat, formerly a member of Machanaim, came to us from Haifa, where he worked in building trade. Moshe Niv, who had learnt the trade by himself, now had a partner. Later, Rafael managed the building crew that built our first living quarters. One after another, people who had finished studying a trade came back to the kibbutz and now wanted to do what they had learned.

We were able to grow field crops, fodder and vegetables on the land we had leased temporarily. That was not the case with an anaf such as orchard, which could only be planted on land that was ours. Michal Avin, who had trained in the orchards of Kfar Giladi, and was now back in the kibbutz, had to wait until we would have a suitable tract of land. So, step by step, we went forward in realizing our aim: a large, well-based, growing, healthy kibbutz on a viable area of land.

improving Naame's looks