The Upper Galilee--Dreams and Reality

I don't recall any details of the decision of the leadership of Netzach to hold a seminar to prepare shlichim to work in the English-speaking countries. The fear that East European Jewry would be cut off for a long time from the rest of world Jewry must have been an important factor. Lasia Galili, who had done movement work in the USA and in England, and who knew these communities better than others, was the initiator of the seminar and planned it. It was decided to hold the seminar in Afikim, that it would last three months, and but five or six candidates for shlichut would participate. I do not recall how the candidates were chosen, or how my name came up. When the kibbutz and I were approached on the subject, the general assembly voted for my participation.

Two members of Kfar Giladi took part (Yaakov Eshkoli and Elka Probt), and one person each from Ein Gev, Givat Chaim, and Anglo-Baltic. One subject on which much emphasis was placed, was learning the English language. The teachers were our Tzvi Weinberg and an architect from England who was staying at Afikim. We studied the language for three hours a day, and in addition, had lots of homework to prepare. There were also lectures on the Jews of America and of England. We had lectures on the political and economic systems of those countries and on their culture. We studied hard like good little children. I don't know about the others, but I felt very much at home in Afikim.

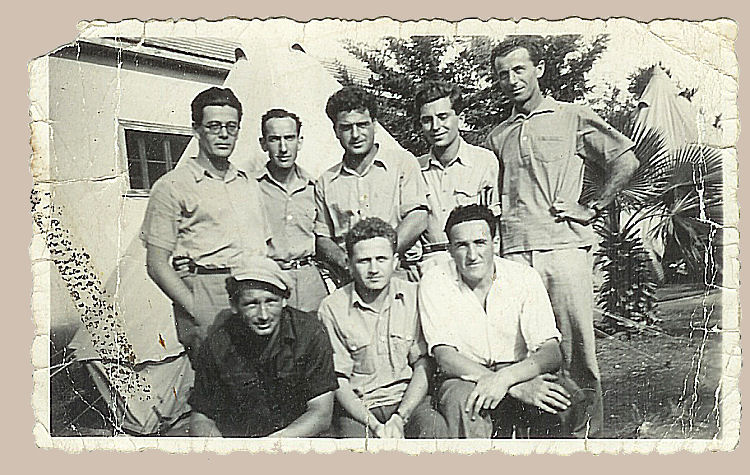

the seminar for shlichim, Afikim, 1940

the seminar for shlichim, Afikim, 1940

I had to leave the seminar on two occasions: one was when I had to appear at my trial in Zichron Yaakov; and the second when I went to visit Natan at Metula. He wanted me to come so that both of us should weigh the idea of sending a work group to Metula.

Metula fascinated me: the beautiful scenery, the peak of Mt. Hermon to the east, the Huleh Valley on the south and the Ayun Valley to the north. The moshava looked like a French village--one street down the middle with gray stone houses on each side, surrounded by fenced-in stone courtyards.

Natan and Gersht lived in the "Snow of Hermon" Hotel, the biggest building in the moshava. The owner, Yankele Brenner, tall and robust, was a well-known character. People who had spent their vacations in the Galilee spread many stories and rumors about him. His wife was a convert and even stronger and bigger than him, and together they made a couple where the one complemented the other. Yankele had a great sense of humor, talked like a farmer and smuggled. The moshava on the border between Lebanon and the north of Israel had a comfortable climate in the summer for vacationers. It was a good climate for fruit trees and the surroundings made smuggling look easy. Yankele's Hebrew included many Arab words and his stories were sprinkled with Arab sayings and proverbs. I am positive that this Yankele Brenner was a unique character.

Yankele made us a proposition--"You fellows rent the hotel from me and run it. The girls can work in the hotel with a few boys to help them. (There were chores, like carrying water from the well to the hotel in buckets loaded onto donkeys, and pumping the water by hand to a container that was raised above the ground.) On the north side of the village, on the actual border, the British have started building a police fort, and more boys can find work there." Both Natan and I could scarcely conceal how attracted we were to Yankele's proposal. We hid our enthusiasm so that he would not raise his asking price. Natan, who already knew of Yankele's proposal, had prepared me, and we arranged that we would act very skeptically regarding the whole plan, and raise doubts about how much money the hotel would bring in. We told him that if his price was too high, Benyamina would never approve of the idea.

Metula, Our Bridgehead to the Galil

From the middle of 1939, our work situation in Benyamina worsened. Actually, aside from those workplaces which we created for ourselves, there was almost no other work option in the moshava. Some opportunity would arise once in a while, but it was not steady. It was even more difficult to find work for the girls, and we would send a group of chaverim quite a distance away to work in other kibbutzim or to train for a specific trade. We thought it best to utilize this period to train chaverim in older kibbutzim in various fields of farming or other trades, and skills which we would need in our own kibbutz.

Shmuel Paltiel studied growing vegetables; Zalman Dolev, raising fodder for cattle; Avraham Berman became a truck driver; Yisrulik Vishkin raised sheep. Later on, we sent a number of chaverim to Kfar Giladi: Eliezer Yisraeli worked with cows, Michael Avin in the orchard, Hillel Avni, an experienced tractorist, hired out to work for PICA to plow their fields in Syria.

With all that, we were worried about the uncertainty of making a living. Some of the chaverim had had the dream of settling somewhere around Benyamina or Caesarea; but that was impossible--PICA already had plans to settle other kibbutzim in the area. In the Mercaz Chaklai (Farm Settlement Center) and the Jewish Agency, they had a long line of kibbutzim waiting ahead of us. At one point, there was a sudden opportunity to settle us at Gezer, where additional land had been purchased with money given by English Jewry. We may even have visited the area. Somehow, just as suddenly, the matter was put aside. The atmosphere in the kibbutz was somber. A minority even suggested that we go back and join Afikim.

With the kibbutz in this mood, Natan and my proposal arrived in Benyamina. We suggested sending a fairly large group, mostly girls, to Metula. We both knew what was happening in the kibbutz, and what the mood was there. That is why we decided to weigh Brenner's suggestion very seriously. There were also rumors that there might be some work there for more men.

We were enthused by the idea of planting a stake in the Galil. The idea grew inside Natan during his extended stay there. For me, only a few days were sufficient to convince me. While at Metula, I talked with farmers and wandered around the moshava and the surrounding area. Maybe we were both slightly intoxicated by the beauty of the scenery and the air. The Hermon in the distance, the green valleys, the many sources of water and the spreading fields attracted our hearts and awakened dreams. We tried to be objective and to weigh the pros and cons carefully. Finally, we decided to present Brenner's proposal to the kibbutz.

I do not recall how much influence our personal recommendation had on the kibbutz. There was a long and serious discussion in the general assembly. Some chaverim thought that running a hotel was a dubious business and was contrary to our ideals. Only honest labor and farming were the proper ways to earn a living. Even those that were for the proposal didn't think that running a hotel and selling drinks or liquor to vacationers whom our girls would serve was such a proper way to make a living. But there the girls would be doing something, and in Benyamina, there was nothing for them to do. I do not know if others thought of that as a way to plant roots in the Galil, but I believe that was in the back of the minds of some of the chaverim, even if it was not said aloud during the meeting.

The general assembly decided by a large majority for sending a large group of girls and some boys to run the hotel in Metula. Among this first group to go to Metula was Frieda Forder, Zelda Sondak, Shoshana Hameiri, Belle Yisraeli and Edith Razili. Bella Yisraeli was the only married girl in the group. Eliezer Yisraeli was living in Kfar Giladi and learning to work with cows. Chaverim said that they often traveled the road from Kfar Giladi and Metula by foot.

The beginning was very tough. The girls worked very hard cleaning up the hotel, which was in a neglected condition. The kitchen and the sanitary facilities were primitive. Water was brought from a spring near the moshava. There they would fill pails of water and tie them into sacks that would hold them on either side of a donkey (a little donkey). Until they were able to rent several rooms, they lived in tents in the courtyard of some farmer. Natan tried to improve the conditions in the hotel, and soon after the first gang came, he started to look for more places of work for others, especially the boys.

the Anglo-Baltic tent camp in Metula

In a rather short period of time the conditions at the hotel did improve. A used truck was bought, on which barrels were loaded to haul the water. Ikie, the American, drove the truck. He had learned to drive in New York (not on a truck). The place expanded and included a restaurant. Already, after one month, guests started arriving; at first, they came singly, and following them, groups from public institutions in the center of the country. The restaurant went quite well, even though conditions there were not too good.

the rear courtyard of the "Snows of Lebanon" hotel in Metula

We had clients coming to the restaurant who were not staying at the hotel. Among those who became steady customers was the head of the northern department of the Jewish National Fund, Yosef Nachmani, and his assistants, Nachum Kremer and Noach Sonin. They came almost every week by car form Tiberias. Nachmani and Sonin were veterans of the legendary Agudat HaShomrim. (The Band of Guards, a group of Jewish guards that defended Jewish property in Israel, was established in Kfar Tabor about 1905. These heroes looked and acted like the Bedouin they fought against. A.M.) Nachmani had become "civilized," and always appeared wearing a nice dark suit and even a tie. Some time later, I saw a photo of him from the days of the "Shomer;" Nachmani seated on a fine horse in his riding breeches, a kefiya (Arab headdress) on his head, a bandolier of rifle bullets across his shoulder, and a rifle in his hands. Sonin had his own style of dress, without the kefiya, but with riding breeches and shiny riding boots. The Shomrim spoke Arabic perfectly. Nachmani spoke excellent English and Sonin spoke Russian.

The Hotel "Snow of Lebanon" run by the Anglo-Baltic kibbutzniks, was the regular meeting place of Nachmani and his aides with the Arab who controlled the Huleh Valley, Kemal effendi. Kemal lived in a large, spacious building in the village of Halsa, the important village in the Huleh. Today, Kiryat Shmoneh spreads over the area that Halsa formerly occupied, and Kemal effendi's house would be somewhere in the RASCO neighborhood. In the then, not-too-distant past, Kemal effendi had been involved in the Arab attack on Tel Hai, in which Yosef Trumpeldor and his comrades fell. Kiryat Shmoneh is so named in honor of the eight men who fell in that battle. After years of hostility between Kfar Giladi and the effendi, he found a way to alter his behavior and now, twenty years later, the effendi had become a "friend" of the Jews.

The land in the Huleh Valley belonged to effendis, rich landlords who preferred to reside in Lebanon. Kemal effendi was their representative on the spot. He took care of their property and collected taxes from the serfs; the taxes were the lion's share of their produce. Kemal, who spoke English, was on good terms with the British police in Halsa. He had the permission of the police to have twelve bodyguards, armed with rifles. The other effendis, who were having a good time in Beirut, were in need of the money Kemal sent them, and they authorized Kemal to sell some of their land to the Jewish National Fund. The negotiations took place at Snow of Lebanon Hotel between Nachmani and Kemal effendi.

Two girls, Zelda Sondak and Shoshana Cooper-Hameiri, served as waitresses in the restaurant. Shoshana, tall and good-looking, made a big impression on Kemal effendi, who would converse with her in English. Zelda Sondak was better acquainted with Sonin.

Shoshana's English and Zelda's Russian helped create a good atmosphere for our important guests. The two waitresses were still new at their trade and did not know Hebrew too well. This was the background to an amusing incident at one of the meals. While Nachmani and Sonin were eating, the latter asked Zelda to bring kesamim (toothpicks). Zelda had no idea what they were, but she hurried to the kitchen where Frieda was in charge, but Frieda didn't know, either, what kesamim were, so she suggested to Zelda to tell the guests that they hadn't cooked kesamim that day. The guests burst out laughing, and that became a much-repeated story of the kibbutznikim at Snow of Lebanon Hotel. There were, of course, repercussions to the meetings between Nachmani and Kemal effendi at the hotel that affected the Anglo-Baltic kibbutz, but more about that later.

The Passover weekend was very successful for the hotel. Quite a few guests came to spend the holiday there and that was encouraging for the girls and for Natan. He wrote to us in Benyamina that the hotel had a pretty good income, but that was not enough for us. From the very beginning, he saw the hotel as a stepping stone to our settling in the Galil. Natan heard that there were still voices in Benyamina who were against sending more chaverim to Metula. In his letters, he expressed his anger with these short-sighted doubters and critics. Natan found work for more men and asked the group in Benyamina to send another group. The call was answered and more men came, including one new father, Shaul Peer.

In our search for jobs we also rented land in Ayun Valley (Lebanon). We bought some mules, a wagon, and some hand implements and started to grow vegetables. Before we grew our own vegetables, we paid a lot of money and bought them from Kfar Giladi. The price they asked for was what they got in Tel Aviv for their products. Yerachmiel Sondak worked with our pair of mules, Galila and Hermona. He did what jobs were necessary in the vegetable garden and also managed to find work hauling manure from the Kfar Giladi barn to the vegetable fields. This was quite a long way off and a steep and rocky descent. They were Lebanese mules, big and powerful. Our chaverim in Metula worked hard, lived in tough conditions, ate poorly, but nevertheless, would go down to the threshing floor of the moshava every evening and sing and chat until late at night.

From Metula to Naame

Towards the end of the summer, Natan asked me to come and visit Metula in connection with something urgent. This was an interesting story: in one of the conversations which Kemal effendi had with Shoshana after he had finished his meal, he asked why does the Anglo-Baltic kibbutz deal with running a hotel, and not farming, like the other kibbutzim. She answered that we had to wait our turn, until the JNF (Jewish National Fund) had enough land to give us to settle upon. Here came the "bomb." "Land is no problem," said Kemal; "I have land in the Huleh that I am ready to rent to you." Shoshana ran to tell Natan, who said that we would like to check that out. The effendi invited them to come to Halsa and talk things over, over a cup of coffee.

I hurried to get to Metula on the appointed day for the visit with Kemal. We went to Halsa at noon and entered his big house. He met us dressed in fine silk pyjamas and sat us round a large copper table. There were Shaul, Shoshana, Natan and I (maybe Ikie also, who brought us there in his truck). We drank coffee and batted the breeze about everything under the sun. Shoshana did most of the talking and answered his questions. He asked many questions about our kibbutz, how many we were, where we came from, and what we did in Benyamina. Kemal told us about the Huleh Valley and the problems he had with the villagers.

I don't recall who reminded Shoshana to get around to the subject for which we had come. Shoshana broached the subject and Kemal said that his younger brother would take us around to have a look at some sections that could be considered for rental. We mounted a small truck which was waiting for us outside the house. Some of his bodyguards were already up there with their guns. We had a thrilling ride through the Huleh with its streams of water on all sides. Here and there, water buffalos wallowed in the beds of streams as we passed by. We saw herds of the buffalos and every so often, we passed by a villager plowing with a wooden plow drawn by a water buffalo.

A herd of water buffalo in the Jordan River.On the far bank stood the village

of Salhieh. Present-day Kfar Blum is on the other bank of the river.

The fields looked good, the water plentiful, and the soil rich. We traveled through quite a large area and Muhammed, Kemal's brother, pointed out which sections belonged to Kemal effendi. It seems that the more we saw, the more we were attracted.

The first village at which we stopped was the village of Naame. Muhammed said that his brother had no land close to this village, and he only stopped there to show us where the JNF had acquired 550 dunams with the assistance of Kemal.The land was on a low hill, south of the village, which stood out only because it was in the midst of a large plain. We were interested only in what Kemal effendi was prepared to lease.

We returned to the house of the effendi in an elevated mood, but there we met with a cold shower. When we asked what price he wanted, Kemal astounded us. We had learned before this meeting what the maximum price was that should be paid for leasing the land. The price he wanted made it clear to us that he was not interested in leasing to poverty-striken kibbutzniks. That evening in Metula, we discussed what we should do next. We decided that on my way back to Benyamina, I would stop in at Nachmani and ask him about the possibility of leasing us the 550 dunams near Naame. I told Nachmani about the meeting with Kemal and he smiled and called Kemal something appropriate for the occasion, in Arabic. When I asked him about the section near Naame, he said it was worth discussing. He suggested we continue the conversation on one of his visits in Metula. I returned to Metula to report on this matter to the others.

When I returned to Benyamina I reported these latest developments to the chaverim there. They also were very interested in the possibility of leasing JNF land in the Huleh. From the latest reports about the hotel, it was obvious that we would not continue running it for long. The best thing there was about the hotel was that it brought us to the Galil and interested us in staying there to settle. We all knew that if we waited in line for our turn without initiating something, we would remain in Benyamina for a very long time. Therefore, we decided that I return to Metula to meet Nachmani on his next visit.

Together with Natan and several others, we sat with Nachmani for a long time. He was ready to help us, but he warned us of many difficulties that would stand in our way. The land at Naame had been plowed but not sown. It should be sown with clover which needed no care in the winter. We would have to be certain that the herds of buffalo of the villagers of Naame would not eat and trample the crop. Nachmani said that the JNF would send an experienced Arab guard to watch over the field, but we would also have to send a guard (at our expense). The two of them would stand watch on a hill overlooking the field all winter (there was a little stone house there where they could stay). In the spring, after harvesting the clover, we could start working the land. At this point Nachmani grew serious. "You cannot stay on that hill in the summer; the area is malaria-striken, and before nightfall, you must return to Metula. The price of leasing the land is no problem; it is a pittance," Nachmani said. I think that Yosef Nachmani really was interested in helping us, but this was also a good deal for the JNF. In this way, the JNF would assure that the villagers of Naame did not encroach on JNF land.

The difficulties that Nachmani mentioned, including that of malaria, did not deter us. Even the problem of traveling every day from Metula to Naame and back did not seem insurmountable. We arranged with Nachmani that I would come to Tiberias to finalize the deal (if the kibbutz in Benyamina agrees).

I don't remember exactly how much time went by before I appeared in Nachmani's office in Tiberias. There an unexpected blow hit me. Nachmani met me with a big smile, as usual, but immediately informed me that the deal was off. "You can't have the land, because Yosef Weitz (President of the JNF) told me that he agreed to lease that land to some Jew who intended to build ponds there for the purpose of growing carp."

I was astounded and must have turned pale, because Nachmani turned to me and said: "Don't make a tragedy of it, we'll find some other solutions." When I recovered my composure somewhat, I recalled that once, I was working on digging a ditch in Nahal Taninim (the Alligator Stream) for a pump. The pump was supposed to fill a reservoir of water where carp were to be stored. An Austrian Jew, Moshe Shwartz, planned on importing carp from Serbia, and storing and selling them in Israel. The Shwartz family had grown carp in Austria and Serbia. Old man Shwartz and his three sons had immigrated to Israel and succeeded in getting some of their wealth out with them before Austria was swallowed by the Third Reich. The oldest son had decided to try to import carp and sell them in Israel.

I do not know how Shwartz found this place on Nahal Taninim. He carried out his plan and several deliveries of carp were made. Our chaverim, and I, myself, worked at unloading the carp, and loading them for shipment to Haifa and Tel Aviv. To our sorrow, this venture of Shwartz did not last long. I hadn't thought of that episode for ages, until that day in Nachmani's office. "What is the name of this Jew?" I asked. "Shwartz," he said, "Moshe Shwartz." Of course, I told Nachmani that I knew Shwartz personally and recounted the episode of Nahal Taninim. "What a small world," said Nachmani. "Let me think about it a bit; maybe we can invent something." When I left him I had the same feeling as when I left Kemal effendi--deep disappointment wrapped in a ray of hope.

All was duly reported to the kibbutz in Metula and in Benyamina, and I waited impatiently for word from Nachmani. After what appeared to be a long time, I was called to Nachmani's office. He said he had waited for Shwartz to visit Naame and then spoke with him. Shwartz suggested that he take 500 dunams and half the hill; and the kibbutzniks 50 dunams and the other half of the hill, and the kibbutzniks would be able to work for him in the fish pond. We would also still supply one shomer (guard). In the spring,when the clover would be cut and harvested, the land would be plowed and the kibbutzniks would start digging the pond. A younger brother, Mordechai Shwartz, would come to live in his half of the building, and oversee the digging of the pond. This arrangement solved many problems for Shwartz, who would otherwise have been in a very isolated situation in the middle of the Huleh with no other Jews around, and it was also good for us, because we would have work and a steady income and some land. The fact that Shwartz already knew us and we him, was a reassuring element for both sides. From that moment on, I, as a kibbutz representative, was very busy buying equipment for harvesting the clover and bailing it and preparing whatever else for our moving up to Naame.

As winter approached, I found out some more information about what our work at Naame would entail. At the beginning of that same year a fish pond had been dug at Kibbutz Dafna, and our same old acquaintance, Moshe Shwartz, had planned it. I don't what sort of partnership there was between Dafna and Shwartz, I only know that it dissolved after a very short time. I also found out that another tract of land in the same vicinity had been purchased and had been given to Kfar Giladi. Nachmani said that that was the kibbutz that was longest in the Galil and suffered from lack of sufficient land, and in Jerusalem it was decided to help Kfar Giladi. Nachmani also said that Kfar Giladi would also send a shomer to guard in thc winter, so that in all, there would be Hamadi, the Arab guard and one from Kfar Giladi and one from our kibbutz. The three were to live in the old house on the hill.

When we had to chose who would be the guard, Moshe Nir volunteered and was chosen. He went up to Metula at the end of 1940. It took him several days to prepare himself (he had to buy a horse and some other equipment for guard duty). On the first of January, 1941, he arrived at the hill of Naame. Later, Moshe told us that when he arrived, Yoske Goral and Hamadi were already there. Yoske's horse stood in a corner of the house and a goat also. The three guards ate and slept in the house. During the day, they would keep a lookout from the hill, and if they saw suspicious movement, they would ride out to investigate. At night, they would go out on patrol, each time at a different hour and in different direction.

I met Yoske Goral and Hamadi only upon my first visit to the hill. Yoske was a man's man, a Galilee "macho" and dressed like a Shomer, with shiny boots. He sat on the horse as if he was born on one. More about him later. Hamadi looked like a very smart Arab and had a good sense of humor, which I could only appreciate with the help of a translator.

Hamadi and family

It was difficult for me to imagine how Yoske and Moshe spent days and nights in isolation in the middle of the valley and far from any Jewish settlement. Their only companion was Hamadi, who sometimes invited them to his abode in the village. Yoske knew Arabic, and Moshe picked it up quickly. They heard from Hamadi an endless number of stories, homilies and sayings of assorted nature, and some juicy Arab jokes. Moshe, tall and an excellent rider, made an impression on the Arabs of the village, who named him Musa-al-Tawil (Long Moshe). I recall even today one of his unusual escapades with a happy end.

When springtime arrived, we bought the equipment for the harvest, all used and quite primitive. We managed to handle the purchase of those items somehow, but when it came to buying a truck tractor with a shovel, a plow and disk, which we needed for digging the pond, we needed a much larger amount of money. I went with Hillel Avni to buy the (used) equipment. We were to need hundreds of pounds (sterling). I went to Bank Hapoalim and I went to Shwartz. I told the bank we needed a loan from them, but that Shwartz would also give us a loan, and I told Shwartz that we needed a loan from him, but that Bank Hapoalim would also help. We got enough funding and bought a Caterpillar 22 with kerosene engine and all the other equipment. I don't know where Hillel found all the stuff.

The winter of 1940 was very hard on the group in Metula. The newness of the little moshava at the end of the world, and the challenge of running a hotel had worn off. They also had difficulty in strengthening their social life and ties, an element which could have helped them greatly. Once we decided to give up running the hotel, people felt that our time in Metula was running out. What still united the group was the wish to settle in the Galil, and the hope that the experiment in Naame would lead to our settling there. We reached the decision to settle in Naame in the summer, despite the warnings of the danger of malaria. Shwartz planned to dig the pond during the summer, and the thought of the work to be done overshadowed the danger of being ill. We waited impatiently for the beginning of the harvest and the transfer of our first group of chaverim to Naame. Before the harvest I went once again to visit Moshe at Naame. From the hill, the field of clover spread a beautiful carpet of rich green color. To the north, between the hill and the village of Naame were the green fields of the Arabs. The hill had an aura of wild beauty.

I walked round the hill and enjoyed all that I saw, but nevertheless, it was obvious that aside from the one stone house, there was nothing that could help us in getting started. Electricity was out of the question. Water-- there was only the shallow, muddy water in the ditches, or clean water from the Jordan, a long distance away. Bread and other products would have to be brought from a distance of several kilometers. The bus stop at Halsa was six km distant on a very poor road. The only doctor was at Kfar Giladi. When I look back to day, I cannot understand how I had the confidence that all would work out okay. Other of our chaverim also told me later, that once they had seen the hill of Naame they had that same confident feeling that all would turn out well.

Givat Naame, The Road to Settlement in the Huleh Valley

When I told about how we first came to Benyamina I described the very difficult conditions in the neglected camp on Givat Hapoel. This chapter on Naame I can open with the statement: We started from absolutely nothing! The first few weeks we lived with nature, and we were forced to deal with the most primitive conditions or whatever we could invent--we were like a bunch of Robinson Crusoes.

filling the water barrel for the first primitive shower at Naame Hill

During the first few years of my aliya to Palestine, the kibbutzim that settled on the Land were called "wall and tower" setttlements. Tens of trucks carrying prefabricated parts of wooden shacks, and many volunteers from older settlements, would help in erecting the walls, the shacks and the tower of the camp area. Not so with us. Our chaverim went from Metula to Naame very quietly. Zelda, one of the first, told me how they reached the village of Naame riding on a wagon hitched to a pair of mules, and rode through the village. They crossed the shallow little stream that ran through the village, passing by the little half-nakcd children and several grown-ups. Instead of the joyful singing of the "wall and tower" settlers, there was the fierce barking of the village dogs.

The beginning was terribly tough, but the spirit and morale of the group was high. Several chaverim from Benyamina also arrived for the historic occasion. Most of them worked at cutting the clover and raking, stacking, drying and baling it with a horse-operated baler. They raised a barrel with holes in the bottom, on poles, and that was the first shower. A sheet of corrugated iron seperated the girl/boy parts of the shower. However, some time passed before the first wooden shacks started to appear. A shed was erected for the mules and horses and some of the equipment.The old stone house underwent some restoration. The place started to look like a settlement--a somewhat decrepit one, but a settlement nevertheless.

A peculiar structure appeared on the scene, which was built by the Shomer, Yoske Goral of Kfar Giladi. All the other workers of Kfar Giladi would return to the kibbutz after work, and return to the fields in the morning. Only Yoske lived on the hill. He built a sort of leanto on stilts, similar to those we had seen in the Arab villages in the Huleh. At the height of the leanto there would be a slight breeze blowing, and there were fewer mosquitoes above than there were close to the ground.

a truck full of building supplies arrives at the Hill

In time, reserve forces from Benyamina arrived. When Moshe Niv got there, quite a few improvements were made. A kitchen and modest dining hall were put up. He made big improvements in the shower and dug a well. At first we drew water by hand, but soon he installed a hand pump.

Moshe Niv also dug something resembling a cellar, in which we could store food (at least for a short time). We brought bread from Dafna, a kibbutz which was established about a year and a half before us. In order to reach Givat Naame, one had to ride through fields and across several small streams. Once a week someone would ride to Kfar Giladi to bring the mail, newspapers and sundry articles. Some time later we established contact with the outside world by means of Morse code, during the day by using a mirror, and by night with flashlight. Kfar Giladi was our point of contact. When the rains were over we would reach Kfar Giladi by way of Halsa, traveling on horseback. During the dry season, it was possible to travel by wagon hitched to mules, and even by truck.

Naame Hill

A Visitor Comes To Warn Us

In the spring of 1939, Dan and Dafna went onto the land; these two settlements were the first in the Huleh Valley. The JNF had succeeded in buying land in the northeast corner of the Valley, far from the marshy area. In Jerusalem, it had been decided to put up a number of settlements on the beautiful lands with the many streams flowing past them to the south. The settlements were to be called "The Ussishkin Fortress" (after the first President of the JNF). I don't know when that period ended and they stopped calling the settlements by that name, but in any case, each kibbutz chose its own name.

That same year there was an attempt to settle a kibbutz on the land of Chaim Walid, on the eastern side of the Valley, close to the marshes. Kibbutz Amir, that had been in the moshava of Hadera, settled there. It soon became obvious that the settlers would not be able to remain in that isolated corner of the valley, that was almost impossible to reach in the winter (rainy) season, and where malaria lurked in summer. The place was abandoned and the kibbutz settled soon after farther north on the east bank of the Jordan. From that time, the JNF decided not to try to put up settlements in the lower stretches of the Valley, close to the marshes. In those days, the marshes began a short walking distance south of Givat Naame. Our settlement on this hill did not make an impression on, and did not convince Yosef Weitz, the President of the JNF. From his point of view, we were unwanted guests there.

Evenings in the spring without the scourge of mosquitoes, made many forget what we had heard about the danger of malaria in summer. The JNF decided to remind us of the facts. They told us the day and the hour of the arrival of Dr. Mehr on the hill. Dr. Mehr, who lived in Rosh Pina, was an expert in malaria epidemics in the Huleh Valley. He worked in a clinic in the large town of Salhieh, on the eastern side of the Jordan (opposite where our packing shed is today). And visited many of the villages whose inhabitants suffered from malaria.

Dr. Mehr visiting patients in an Arab village in the Huleh Valley

A number of us gathered and waited tensely for this visitor, who was likely to make things complicated for us. I recall his visit vividly, even today. It was a dramatic event in our stay at Namme. He was a lean, tall, "Gary Cooper of the Galilee" sort of person. He sat down in our midst and said, "I have come to warn you that you will not be to stay on this hill in the summer. When it becomes warmer, the mosquitoes will attack you in the evenings and nights without mercy. You will all come down with malaria."

If that is not exactly word for word, it is definitely the content of what Dr. Mehr had to say. We didn't ask questions and I believe we didn't say anything at all. He rose, said goodbye, and walked out. We sat stunned, and before we could react, he knocked on the door and came back inside. "I warned you because the JNF asked me to, but as one who has worked in this Valley for a long time, my word to you is: It will be difficult, but if you are stubborn--you will hold out." He was gone We did not burst out in song, but this Dr. Mehr warmed our hearts and strengthened our spirits. I never met him again, but I heard that he was mobilized into the British Army and worked as a doctor for British troops in southeast Asia. In the course of time, Professor Mehr became a world-renown authority in his field.