My Aliya--The Start of a Long Journey

My Baltic chaverim introduced me to our English chaverim, who had come to Afikim via Kinneret, where they had spent two years, since 1936. I believe now that from the very first encounter with the English, I had the feeling that our union with them would succeed. That may be because when I met them, they were already old-timers in Israel. They had acclimatized and gained experience in different types of work. Only later did I learn that despite that, there would still be many difficulties and many problems to overcome. An important factor was that both the English and the Baltic groups wanted the union between us to work, and realized its importance.

While I was still in Vienna, I had received a letter from Borka, and he told of the decision of the managing committee of the Netzach movement to join a Baltic group of Netzach members with an English group, some of whose members were already in Israel. More of them, and more Latvians, were expected to be coming soon. I was interested in getting to know not only the English and Baltic members of our group, but also the Russian members of Afikim and the members from other smaller contingents that made up Kibbutz Afikim. There were individuals that came from Syria, America, and other countries, and how each one got to Afikim was interesting and unusual.

By the time I arrived at Afikim, it was already a well-known success story. The agricultural base was well-developed. They had a large dairy barn, fields of clover, etc., for fodder, a large chicken run, banana and grapefruit orchard, a vineyard and irrigated fields. Most work was done with horses, but they also had several Caterpillar tractors. Another group of members worked in the building trades that they had learned before settling at Afikim. The kibbutz also developed a transportation branch, owned a number of trucks and opened a garage. Afikim also had an industry.

Such a state of affairs allowed us some choice of work experience. I for one, was not only impressed by the achievements in farming and other things, of the kibbutz, but also by its social framework. The society was close-knit and alive, with lots of cultural activity. There was a drama group and a choir. The kibbutz was aware of what was happening around it, and knew how to celebrate the traditional holidays within the boundaries of the kibbutz lifestyle. I felt an aura of optimism there.

The strength, ability and creativity of a society are functions of the quality of the individuals of that society. I recall that during my stay at Afikim I marveled at the wealth of the creative abilities of many members of the kibbutz. Even today, I could fill pages describing many individuals who captivated me. I am not talking only about the so-to-speak "important" members, like those who were shlichim to the movement and whom I already knew, such as Lasia Galili, Aryeh Bahir, Elik Shomroni and Yosef Yizraeli, who filled many important positions before and after the creation of the State. There was also blond Mitia, barefoot and with touseled hair, who initiated the building of one of the first large industries in the kibbutz movement. His wife, Bertha, was the work manager of the factory. There was small Buzhik, with "hands of gold" and the brains of an engineer. There was good-looking Mulia, an excellent educator and active in the cultural life of the kibbutz.

I met many interesting members in the various branches of farm work, and there was Caleb, the big Yugloslav in charge of the horses. I knew tall, lean Moshe Wolfson, the likeable American truck driver who reminded everyone of some American cowboy hero. I recall Clara Galili, one of the founding members of Afikim, and tiny Yehuditka--they were both in charge of the kitchen/dining hall. Gentle Shura was the kibbutz nurse. Tamara, with the beautiful eyes, had some complicated romance and reminded me of Anna Karenina (but without the tragic ending). One tzabar (cactus, meaning, born in Israel), Chaim Hurwitz, raised fodder for the cattle but was expert on Hebrew literature, and could quote from the Hebrew poets from memory. Chaim and I met when we worked in mispoh (cattle fodder) together with Shaul, who had grown up in Tel Aviv. Shaul was from the Noar Oved (working youth) movement, and Chaim was from Machanot Olim (similar to Boy Scouts). Chaikel Rosen and Dudik (David) Fradkin were "Ghaffirim" (Members of the Jewish Supernumerary

I looked at Afikim though the eyes of a new immigrant, a graduate of an idealistic youth movement. I was enchanted, excited, and I guess, somewhat naive also. I knew that the kibbutz was to prepare us for our future not by lectures, but by work and by living kibbutz life. I'll now tell a bit more about Afikim as I was told by several of its members. This has bearing because it served as a lesson for us in many ways when we were building our Anglo-Baltic kibbutz and laying the groundwork for Kfar Blum.

The founders of Kibbutz Afikim were 19-20-year-old Russian members of the Hashomer Hatzair movement who made Aliya in the early 'twenties. They dreamed of founding a kibbutz for themselves and for their friends who were still in Russia, many of them in prison or exiled to the Urals. The first ten went up to Buzia, near Rosh Pina, where they worked at harvesting tobacco. In the fall of 1924, they defined themselves as Kibbutz Hashomer Hatzair from the USSR. From then on, they wandered from place to place and grew in numbers. There was a geat deal of unemployment then in the country, so when the tobacco harvest was over, they went to Emek Yavniel and from there to Afula, working at various jobs. In 1926, the young kibbutz had grown too large for the work available, so they had to split up and look for work in several areas. One group went to Haifa, another to Zichron Yaacov, to Tira, and one group worked on the Yarkon River. The unemployment and the fragmentation of the group caused the despairing ones to leave. Those that remained rethought their position, and decided they must reunite into one group. The place to unite was Kinneret, in the Jordan Valley, from where they went to work on the hydroelectric project at Naharaim.

Some members left the kibbutz while it was at Kinneret, but the remainder were more determined than ever to found a kibbutz. Land and money were in short supply at the institutions responsible for land settlement, and it seemed that the kibbutz would have to wait a long time, but this time, luck was with them. The four older kibbutzim in the region, the two Daganias, Kinneret and Beit Zera joined forces and built a pumping station. This gave them the opportunity to irrigate all their land, and they were able to do with less. In this way, Afikim received 500 dunums, which was enough for a start, but they still had no funding. The kibbutz made an exceptionally courageous decision and decided to settle and build the new kibbutz on its own. The decision taken, they acted and developed from the outset several branches of work which gave them a cash income until the agricultural branches would start to pay for themselves. Some members went to work outside the kibbutz, some started a trucking industry. They started building the kibbutz in 1932, and the name Afikim (river beds) was chosen because on the west was the River Jordan and on the east the Yarmuk River.

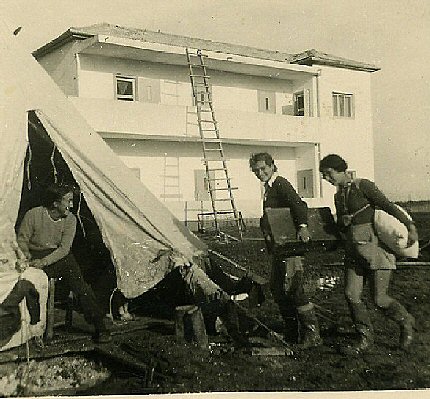

Tents of the Training Camp (hachshara) at Afikim

The tent of our group was at the edge of the kibbutz, near the barbed-wire fence surrounding the kibbutz. I didn't mind living in a tent, but it may have been uncomfortable for some of the members to live in this small space with nothing but a couple of beds and a few wooden boxes. What was difficult, was getting to the dining hall after a rain, as the soil was heavy and did not absorb the water quickly, so that tramping through the mud was messy. We were all given rubber boots, but I recall that there were times when it was simpler to take off the boots and roll up the pants and walk to the dining hall barefoot. We would never think of missing a meal, nor would we give up our cup of tea, with bread and jam, after work was over. It took some time to get used to the food. "Six-seven olives are worth one egg" we were told; but no one would give up their egg for the olives. I liked the dining hall shack, bustling with the sound of people. The diners at the tables would change continuously, as those finished eating left the table and others took their place. In this way you meet people that you did not work with or have a chance to meet otherwise.

Life in the mud and tents at Afikim

The members of our Garin (nucleus of new kibbutz) were assigned to the various work branches of the services. Not all were able to find a steady place of work. I worked in mispoh (raising green fodder for the cattle) and enjoyed not only the work, but also the gang I worked with. There were three men and a woman, Shalom Barzilai and myself from the Garin. I already mentioned Chaim Hurwitz and Shaul Peer; the third was Benny Kirshon, a very likeable "Litvak" (someone from Lithuania). The only woman was Sima, who came from Tallinn to Afikim. Shalom had worked in mispoh in Kinneret and I did my best to keep up with him. We cut the fodder with scythes, then stacked the cut fodder and loaded it onto a wagon. On a rainy day, the work was especially difficult, and the wagon would get stuck in the mud. Sometimes the work could get boring, but being in the company of Chaim, Shaul and Benny was never boring.

In the springtime, everything changed. Not so many workers were needed in mispoh and I went from one job to another. In the trucking branch there was what we called the job of "second driver." The second driver sat in the cabin of the vehicle and helped the driver load and unload. In dangerous periods, he carried a weapon to protect the driver. Even in those days, all manner of foreign words had entered the Hebrew language, such as kugel lager for ball bearings and "puncture" for puncture.

When they started doing repair work at the Naharaim Power Station, I went along as part of the Afikim crew. The work was not difficult, but it was boring. I did do some hard work when I dug foundations for pylons which ran from Naharaim to Beit Shan. We dug the holes in pairs and my partner was Yaki's father, a nice Yugoslavian who ordinarily worked in the carpentry shop. We were paid per hole, so we worked hard and we made good money.

When the harvest was over, a group of workers was put together to work in the Beit Shan Valley and bale straw for Moshav Beit Yosef. The gang consisted of an experienced tractorist, four people who tied the bales, two on each side of the baler, and two pitchfork men, who dished the straw to the baler pickup. I worked with the pitchfork. We were paid "by the bale." The tractor and baler were brought to Beit Yosef and remained there until the fields were finished. We traveled back and forth on the "Emek Express," a train which was a relic of the Turkish rule in Palestine. The tractorist was David Cohen, "The Litvak." He made an "arrangement" with the Arab conductor, who gave us used tickets at a cut-rate price, so that we saved some money on the fare and he made a little extra on the side.

Afikim tried to arrange permanent places of work for the members of the Garin. We understood that there were at times difficulties and we could not all be put in places where we could learn a trade. In any case, it is not easy to become expert at any trade in a short time. We realized that the most important thing to learn is how to work well at any job we were given. I myself was not too sorry that I changed jobs fairly frequently. While at Afikim, I worked in the winter in mispoh and in the spring at Naharaim and Beit Shan. I also worked for a few weeks at Dagania and Kinneret. In the fight against insect pests in the orchards, all the kibbutzim joined forces and made up a mixed group that went from one orchard to the next. We would cover the trees with tents and the trees inside would be sprayed and the tents moved to other trees. While at this job I met new immigrants from many different countries. I also worked as a second driver a few times and traveled as far as Haifa, where we went to a movie, and spent the night at Haifa. These various jobs tempered me, and when faced with some new or strange job, I had no fear of doing it.

Once, when I was second driver to Matityahu Ashkenazi on a trip to Haifa, we had an incident which describes the feel of the period. Mati was a non-communicative sort of person and rarely spoke more than one sentence to a conversation. As we were leaving Haifa after unloading and loading the truck, we came to a little square not far from the railway station, when Matityahu said, "We have a puncture and it is dangerous here; take the gun and stand guard while I change the tire." I got out and stood with my back to the truck while Matityahyu went to work on the tire. I was not worried by his remark that this was a dangerous spot until two British policemen, who were patroling the vicinity, ran over to us and also stood guard with me. From that moment I thought maybe I should be worried. Matityahu finished changing the tire and thanked the two policemen; we got back in the cabin and took off. "We were lucky they came along," said Matityahu, and did not utter another word until we reached Afikim.

Another "security" occurrence that I recall is the settling on the land of Kibbutz Hanita, on the northern border of Palestine. Several members of Afikim took part in that event and told us about it when they returned. (This was a very exciting and important episode at the time, A.M.)

At Afikim, we not only worked, we also lived and had a good time there. Once, on the 11th of Adar, we were taken to Kfar Giladi. From there, I saw for the first time the snowy peaks of Mt. Hermon and the green valley of the Huleh. On weekends, we went for hikes in the hills around us, swam in the Kinneret, and generally enjoyed ourselves.

The holidays at Afikim were very nice. The Passover Seder was particularly impressive. Yehuda Sharet, Moshe Sharet's brother and a member of Kibbutz Yagur, was the cultural and musical "father" of the Kibbutz Seder, as it was then conducted. At Afikim, they had an excellent choir; there would be reading from the traditional Haggada and from Zionist and classical poetry; the atmosphere of the holiday was just very positive. Years later, when we were in Benyamina and even on the hill of Na'ama (that is where this Garin eventually settled, A.M.), we tried to continue the tradition of the Afikim Seder, as we old-timers had experienced it.

Summer was more difficult for us than winter. The heat of the Jordan Valley is hard to get used to. We would start work early in the morning, and take a long break at noon; then finish the day's work when the heat was on the wane in the afternoon. It was quite impossible to rest in the tents at noon, and we were assigned to members' rooms for that break. There, we would cool off with a shower and sleep on the floor. The summer heat sapped our strength and energy; we English- and Baltic-born would take sick more easily in the hot climate; some would break out in sores and others had stomach problems. We managed to overcome this obstacle also, and towards the end of the summer, we started to argue and deliberate on the future of the Garin.

Until the second half of 1937, the members of the Netzach movement were concentrated in four kibbutzim: Afikim, Kinneret, Kfar Giladi and Kibbutz Batelem (as Ein Gev was called when it settled on the land). These kibbutzim were included in the framework of Hakibbutz HaMeuchad, but were in a sense a separate entity in that framework. All these kibbutzim were interested in growing larger and in building some sort of industry, not only being dependent on farming. They also wanted to grow and absorb new members. However, the Netzach members did not want to accept the political ideology of the "Guru" of the Kibbutz Meuchad, Yitchak Tabenkin, and were closer in ideas to those of Ben-Gurion and Berl Katznelson. They insisted that every individual have the right to choose his own political outlook. The secretariat of the Kibbutz Meuchad did not direct new immigrants to the Netzach kibbutzim, and the Netzach movement saw to it that its own new immigrants would go to Netzach kibbutzim. Almost all those who came to Palestine from the Baltic countries during 1937 were sent to Ein Gev.

The joining and mixing of Garinim from different countries was a usual occurrence in the kibbutz movement. Nevertheless, both sides were a bit worried about how the Anglo-Baltic blending would work out. We were aware of the differences in cultures and language, and aside from the basic ideal of all wanting to create a new kibbutz, there was little else in common. We hoped that all would work out well, but we had our qualms. During the winter, and while living in tents, it was a little difficult to organize social activities, as we had no place where enough of us could gather under one roof, and tramping to some other place in the kibbutz was difficult because of the mud. In the spring and summer, that situation improved, because we could all go swimming in the Kinneret, or gather on a lawn somewhere for talking or singing, etc. We started to get to know each other; new people joined up with us. Some were new arrivals from our countries and others were "singles" who happened to fall in with our group. I was one of the few who saw that despite the difficulties that there would be in the blending (or clashing) of our cultures, this mixture also offered the possibility of enriching the life of our future society from the social-cultural point of view, and would add spice to our life.

On bales of hay at Afikim

As the Garin grew, several couples were formed, particularly among those that came from Kinneret. Among them was the first mixed couple, Shalom Bordoli from London and Leah Deutch from Dvinsk, Latvia. There were also some Baltic couples. In general, there was the feeling that we are getting older.

In Afikim we felt very comfortable. We liked the place and the people and they liked us. Although we were "temporaries," we were known to all and we took an active part in all their cultural activities. The Balkan contingent had the biggest repertoire of songs (which we usually sang a little louder than necessary). The English taught us to sing in a more civilized way. Tzvi Weinberg, one of the English fellows, later became an excellent choir conductor.

In the latter half of the summer, we started discussing the future of the Anglo-Baltic Garin. At the time, there was a group of Germans who were close to Netzach ideology and wanted Netzach to send them a group. They were at the time in Hadera. The Netzach leadership was interested in having the Germans join the movement and thought that we might be a good group to join the Germans and bring them into Netzach. We were divided; some wanted to join the Germans and others, including me, wanted independence. After more discussion and an exchange of visits, we had a vote, and the majority decided not to join the German group. We wanted to "make it on our own."

The Anglo-Baltic Kibbutz

Once the decision was taken, the leadership of Netzach and Yosef Yizraeli, the treasurer of Afikim, helped the Garin make contact with the necessary institutions regarding where we could make our temporary home in one of the Moshavot (rural communities). Yosef Yizraeli suggested to the Garin to choose its own representatives. I was chosen to represent the kibbutz in dealings outside the kibbutz, and Borka was chosen as secretary. (In kibbutz, the secretary is like the president or mayor of the settlement.)

The Garin knew about other Garinim and how they live in larger or smaller Moshavot spread over the country. There was usually a special camping area with some wooden bungalows and maybe a small house or two, and one larger building that could be used for the common kitchen/dining hall. Showers and toilet facilities were usually in a separate building. In some of these camps, some of the newer members lived in tents. The kibbutzim and garinim lived in these "temporary camps" until they were given land to settle on (usually by the Jewish National Fund). When the first kibbutz in the queue would receive land, it would evacuate the temporary camp and a new kibbutz would take its place in the queue for permanent settlement.

I travelled to Tel Aviv with Yosef Yizraeli to meet the Agricultural Board. (This Board, directed by the legendary Avraham Harzfeld, was essentially the body that decided which kibbutz would settle where, and when. A.M.) At this very first meeting, we were offered a spot for our camp in the village of Benyamina. Another kibbutz was moving out of that spot soon and we would be able to move in. Benyamina is in an excellent area of the country, on the high road between Haifa and Tel Aviv, and the climate is comfortable. Buses ran by often and there were other moshavot nearby, and most important, the farmers grew a variety of crops and there would be enough work the year round. There was also a quarry of Solel Boneh in the vicinity which needed workers. The camp itself, we were told, was not in too good condition, but with time, we could make improvements. The camp was located in an area of workers' quarters called Givat HaPoel, on the northwestern side of Benyamina.

It was suggested that we go visit the place ourselves, talk to some of the people there and get an impression. We sort of had the feeling that they were a bit too eager to "sell" us the place. We were told that most of the Jewish farmers in Benyamina use Arab workers, and that some even have Arab workers living on their farms. During the riots of 1937, some of these Arab workers were fired and others left of their own volition. The Moshava needed workers and the farmers had asked the Agricultural Board of the Histadrut (hereafter, Agricultural Board) to send them men, and the Agricultural Board was anxious to introduce Jewish labor into the Moshava.

Yosef and I returned to the Garin and reported what we had learned. The Garin decided that the first thing to be done was to visit Benyamina. I and several other members were appointed as a committee to visit the site and report to the rest of the Garin. At Benyamina we were met by the head of the workers' council of the Moshava, a nice guy named Gersht. He accompanied us and showed us around during our visit. The Histadrut (Workers' Labor Movement) had helped about a dozen veteran workers in Benyamina to own their own houses, and that is what Givat HaPoel was. The houses were new, small but nice, and there were small gardens and lots of trees all about.

On the other hand, the camp we were supposed to move into made a very poor impression on us. The building that was meant to be the kitchen/dining hall was neglected and in poor condition. A group of tents, similar to the ones we lived in in Afikim, stood not far from the dining hall and there were also a few buildings, each one with four rooms. These were still inhabited by people who were soon to be transferred to houses elsewhere. One family, from the former kibbutz Hafetz Haim, was also still living there.

The low hill where our camp was located was not so bad. The view of the foothill of the Carmel range to the north was quite beautiful. We walked round it, and crossed the Taninim Stream to see the quarry. We checked out the town intself, which consisted of the main street with the houses of the farmers surrounded by enclosed courtyards on each side. There was also a post-office, a little general store, a schoolhouse, a small synagogue, a train station, a smithy, and a small restaurant which also served as the "Egged" bus stop.

We also visited the other new neighborhoods of the Moshava. There was the Georgian settlers' area, and the German immigrant area. The Georgians were mostly workers, Gersht told us, but the Germans were not so young and had formerly been lawyers and other professionals; now most of them had small chicken runs or some other facet of agriculture that they developed to support themselves in their new homeland. On the other end of the Moshava, we visited the cowbarn. This was an old building which had once been a cowbarn, but in which now lived a group of Yeminite workers.

Gersht told us about the farmers and other inhabitants of the Moshava. He said that there were some "progressive" farmers that were willing to do without Arab laborers, but most of them preferred to work with them, and were only interested in using the cheapest labor possible.

We returned from the visit in Benyamina satisfied but worried. The rural atmosphere of the Moshava, with its mixed population, seemed good, and the location was pleasant. What worried us most was the neglected appearance of what was to be our camp area. In our discussion, we decided to clarify with the Agricultural Board what could be done to better the camp facilities, and if, in addition to tents, we would also have several of the rooms in the houses at our disposal.

The second trip to Tel Aviv with Yosef Yizraeli lasted two days. We visited several departments of the Agricultural Board and some other institutions as well. We were promised that improvements would be made in the dining hall, and that we would also be given a number of rooms. We were also promised help in other areas. Yosef introduced me to Pinhas Koslovsky as the man responsible for granting loans for small farming through the agency of Nir Shitufi. Pinchas heard me out patiently, and said that although he no longer deals directly with these matters, he would bring it to the attention of the people concerned and see that our needs be met. This same figure was later known as Pinchas Sapir, the Treasury Minister of the Golda Meir government.

We stayed overnight in Tel Aviv, where I made the acquaintance of another institution, the "Barash Hotel." This was a small, two-storey building on Yavne Street. The owner was Yosef Barash and he informed us that his hotel was THE HOTEL for everyone from the Jordan Valley, in Tel Aviv. There were other hotels like this one, and I assume the others catered to other areas of the country. At any rate, from that day on, if I stayed over any night in Tel Aviv, Barash was the place. One day, when I was shown to my room, I noticed that the sheets and pillow had been used and I remarked to Barash about that. "Okay," he said, "I'll change them, but why should a newcomer like you worry about sleeping in the same bed as Yosef Baratz?" (Y.B. was one of the founders of Kibbutz Dagania, the first kibbutz, and one of the leading figures of the Labor Movement.) But enough of memories of Hotel Barash and back to my story.

On the way back to Afikim, Yosef said to me, "Remember, not all promises can be kept. I'll go with you until you feel you can manage for yourself." Yosef and I appeared before the Garin, and Yosef recommended that we agree to the proposal of the Agricultural Board and go to Benyamina. He said that despite the poor condition of the camp area, if we confront the necessary institutions forcefully enough, we will get what we want. More important, it seemed that Benyamina was a Moshava that offered decent opportunities. I also said that the Moshava looks good to me, and even attractive. At that meeting the Garin decided to choose Benyamina as the place where the Anglo-Baltic kibbutz would establish itself.

That summer, the Garin was strengthened by the absorption of new members who arrived from England, Latvia, and Lithuania, and in the few weeks that remained prior to our moving out, several people from Afikim joined us also. We were glad to have Shaul Peer and Sara join us, as well as Bella R. whom Afikim loaned us to help Beba to set up the kitchen. Shaul, who came to Palestine at a very young age and had grown up in Tel Aviv, was an experienced farmer, well-versed in self-defense matters, and a graduate of the Labor Youth movement, which was close to our own. We knew he could help us acclimatize to the country in many ways. Sara was born in New York City and had made Aliya in 1932. She was a professional nurse and had studied at Hadassa Hospital in Jerusalem. Had she not joined us, we would have had to ask Afikim to assist us in that field also. Sara, an intelligent and serious girl, and already a Vatika (veteran, experienced) in Palestine, was a godsend to us. Shortly after we left Afikim, Chaim and Lami Beitan also joined us. Chaim was one of the first Americans in Afikim, and Lami was an Olah Chadasha (new immigrant) from the Habonim movement in America. She was a pretty and lively girl with much charm.

With the feeling that we were larger and stronger than ever, we made preparations to leave for Benyamina. The Moshava was interested in our arriving in time for the citrus harvest. We decided the date of our departure.

As a reminder, in reaction to the bloody outbreaks of 1936-1938, the settlement agencies established new settlements. These were known as "Choma uMigdal" (wall and tower) settlements. In this spirit of determination and spiritual uplift, our departure became an important event in the life of Afikim. The members of the kibbutz did everything possible to help us and supply us with whatever we would need. They gathered chairs and tables for our dining hall; primusim (kerosene burners) and pots for the kitchen; and they filled boxes with food that we would need for the first few days. They prepared a bundle with first-aid supplies. We felt they wanted to take care of us, as parents do for their children. We were impressed and touched by their attention. Along with all the excitement and uplift, there was also a feeling of sadness in our departure. The departure of our Garin from Afikim was described very many years later in a brochure published in honor of the 70th Anniversary of Afikim, by one of their members, Yisrael Chofesh. He wrote:"...It was not lunch or supper time, it was not a meeting and not a holiday, but the area was crowded with chaverim. Why did the gong ring (members would be called to meetings or to meals by banging on a piece of metal. A.M.) Why did the siren go off at 9:00 a.m.? The news is spreading like lightening, the Garin Anglo-Balti is going out to settle on its own. The members left off in the middle of their work and crowded round the loaded trucks in the garage area. The hour had arrived, which we had all looked forward to. Someone started to sing, hand joined hand and soon there was a Hora (circle dance) in full swing. 'The chain is unbroken..' " This somewhat emotional description was typical of the spirit of that era, but that is how the old-timers of Afikim remember our departure. We left on 3 trucks, the new "Kibbutz Anglo-Balti."

Dancing a Hora outdoors

Goodbye Afikim, Hello Benyamina