Childhood and Youth

My mother, the daughter of the Rabbi Gavriel Ilion, was one of six children, three girls and three boys. According to my mother, my grandfather was an "enlightened rabbi." All three boys received university education. The eldest became a psychiatrist, the second, a pharmacist, and the youngest, a general practician. My eldest aunt was a graduate of a German seminary for girls and my mother was sent to Kiev, Ukraine, to receive training as a dental technician.

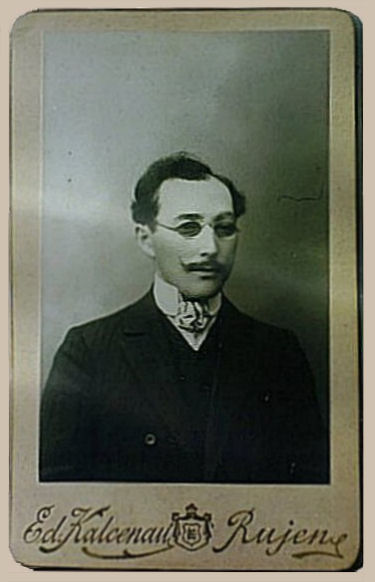

My father, Joseph, the son of Eliezer Levitan, I did not have the good fortune to know. While I was still a very young child, my father had to flee from the house and from the town and was never again seen by anyone in the family. My father was born in Shavli, Lithuania, and was well-educated and became manager of a candy factory. From stories I heard from my mother and other relatives, and from the few pictures we had in an album, my father was a serious-looking man, well-dressed, and respected by family, neighbors and by the workers in the factory, who considered him demanding but fair and just, as he extended to them a helping hand when they were in need.

Joseph Levitan, Nechemia's father

It was only some years later that I learned why my father ran away. It seems that this quiet, orderly man and factory manager was, indeed, an underground revolutionary. Joseph Levitan, manager of a candy factory, succeeded in smuggling weapons into Latvia from a foreign country for the use of the underground, in crates that were presumed to contain raw material for the factory. When his friends were warned that his ruse had been discovered, they smuggled him out of the country. My mother never spoke of my father's escape and never mentioned anything of this whole episode. The Tsarist counterintelligence was well-known for its cruelty, and surely must have made efforts to obtain information about him. My mother said nothing and my big sister warned me not to bother her with questions on this subject.

Nechemia's mother, Bertha, with his sister, Lena

Before long, the German Army approached the border of Latvia and many Jews started fleeing eastward into Russia. My three uncles decided to leave Ruyene and took my mother and her children and my grandmother on my father's side, with them. I don't know how my uncles managed to make the long journey from Latvia to Perm, in the foothills of the Urals. I was too young to remember.

I do recall quite a bit about our stay in Perm, which was a fairly large city on the banks of the Kama River. The city looked to me more like an overgrown village. The streets were paved with large round stones, and there were many two-storey wooden houses, but similar to the one-storey houses that villagers built. In winter, the Kama River would be covered with ice over its wide expanse. In the spring, we would hear terrific noises and I and all the children would run to the shores of the river to see the ice breaking up and the large chunks would float downstream. Farther down, the Kama would flow into the "Mother Volga," as that river is called by the Russians. The Kama River was the lifeblood of Perm, and connected her with central Russia and by way of the Volga, with the south as well. During the rule of the Tsars, prisoners would pass through Perm on their way to Siberia. During the rule of the Communists, the Perm Prison became infamous.

Our life in Perm was difficult after the Revolution and during the Civil War. My mother told us that our uncles, the doctors, helped us a great deal. Villagers who had need of them paid them in agricultural produce, flour or bread, potatoes and sometimes meat. My enterprising and energetic mother started a little household industry using materials she received from farmers and from her brother, the pharmacist. She manufactured soap in the bathtub and sold it or exchanged it for whatever we would need. I remember that we had a large courtyard in which we used to play, my sister watching over me, and my grandmother keeping a watchful eye on both of us.

While at Perm we received the awful news that our father had been killed in the Civil War fighting against the Poles. Friends wrote my mother, saying that my father had been the "Politruk" (political guidance counsellor) of his unit. They arranged for all of us to ride by train to Petrograd. My mother agreed to make the trip if they would also help us in Petrograd, and they did promise to do so. When I asked her once why we left Perm, she said it was to be nearer to Latvia and Estonia, where her sisters lived, in the hope of being able to visit them as soon as would be possible.

We parted from our three uncles and never saw them again. Once, when I was in Moscow in the 'fifties (I served in the Israel Embassy there), I heard that my eldest uncle, the psychiatrist Professor Ilion, had passed away a short time previously in the city of Gorky. I never heard of the other uncles.

My mother started out on the long journey with tears in her eyes. In those times of unrest and upheaval, every journey was fraught with danger, and this parting was to be forever. We were given a whole freight car for ourselves. The uncles helped us load all our furniture and kitchen and bedroom articles. We could sleep on mattresses and in general, conditions were not bad. The trip took a whole week, as we had to traverse all of European Russia. We stopped at many stations along the way, and at some we were delayed for many hours. Sometimes, weather permitting, we opened the heavy door a bit and watched the scenery which passed by the train: forests, fields, rivers and streams, and miserable villages with their huts and hovels.

In Petrograd, at the huge train station milling with very many people, we were met by total strangers. They took care of all our furniture and moved it over to a big apartment building and led us to a large apartment on one of the upper floors. The apartment was so large that we could not afford to heat it all in winter, so the extra rooms were closed off and we only used and heated what was necessary.

I remember our address in Petrograd to this very day. We lived on the island of Vassilievski, that the Neva River encircles on all sides. The island was attached to the center of the city by a long bridge. The isle of Vassilievski is a very nice residential area. The main streets run from east to west, and include three wide boulevards known as "the Small," "the Medium," and "the Large"! These were divided at right angles by smaller streets that were numbered. We lived on 6th St., house number 43. An electric tram ran along this street and the noise of its warning bell and of other traffic filled the air.

This was a period of economic depression and there was a lack of many essentials. The First World War and the Revolutions left many scars on the face of the country. I to this day do not know how my mother managed to support a family of four souls. We must have received aid from some institute or organization to move from Perm to Petrograd. Perhaps my mother also sold some of the family valuables from time to time. My resourceful mother carried on a relentless war of survival without our being aware of her difficulties. She was always a calm and smiling personality.

The city was only starting to reorganize and recover from the street fighting of the revolution. Slowly, the new regime renewed the various city services. We had water in the apartment, but the elevator did not work, nor was there central heating. We, like all our neighbors, bought a small wood-burning stove for heating and cooking. From the stove an exhaust pipe extended to a window, so that the smoke could escape, and this pipe also served to heat the apartment. We would search for wood in abandoned houses and wherever else possible, my sister and I became experts at this trade which supplemented the small amount of wood that Mother could afford to purchase.

Wandering the streets of Petrograd kept us occupied and interested. The city, charming in its beauty, was founded by Peter the Great in the 18th century. He chose the area where the Neva River spills into the Gulf of Finland. Petrograd replaced Moscow as the capital of the country, and became a "Window open to the West." Peter and the Tsars that followed him brought architects from the West who planned its streets, boulevards and bridges. The buildings were built in the French style of the period. I was fascinated by the city as a boy of seven, so much so, that 32 years later, when Beba and I visited Leningrad (formerly Petrograd) I was still amazed by its beauty, the statues and the squares, the Winter Palace and Kazanski Sobor Cathedral, which even the anti-religious Communist regime was careful to preserve. I even remembered the Lion statues on the bridge. I led Beba from our hotel in the center of the city to 43 6th St. on Vassilievski Island, and went everywhere in the city without having to ask for directions.

My childhood Petrograd period was drawing to an end. One day my mother came home very late and gathered us round the table. She told us that soon we would leave Petrograd for the city of Riga, capital of Latvia. From Riga, our grandmother would sail to America, to our two aunts, our deceased father's sisters. We, Mother, sister and I, would continue to Tallinn, capital of Estonia. My mother's oldest sister, Debora, lived there and she would help us settle in Tallinn. Some time later, our mother told us that some of her husband's friends had arranged to get them moved to Tallinn, and a Jewish-American philanthropic organization arranged for our grandmother's passage to the USA.

Shortly thereafter we left Petrograd for Riga (this time by passenger train, not freight train). As soon as the train crossed the border we were met by a tall, elegantly dressed man. He smiled and addressed my mother in Yiddish. I, Niuma (as I was called by my Russian diminutive) decided immediately that this was our good uncle. Actually, he was the representive of the American Jewish organization, and he helped us in every way possible. We were given train tickets to Riga, he had a man transfer our baggage from train to train, and brought us lots of food to eat on the trip to Riga. I probably remember all this so well because of the impression that all the delicious snacks made upon me. He stayed with us until the train pulled away from the station and then waved us on our way.

At this point, I shall stray slightly from my story. More than 43 years after that day at the Latvian border, while I was working at the Israeli Embassy in Washington, I became very familiar with a leading representative of the JDC (Joint Distribution Committee, commonly known as "the Joint"). This organization did a great deal for needy European Jewry after the First and Second World Wars from its inception in 1914. During the 'sixties, when I was sent on behalf of "Nativ" (an underground organization that opened a route--nativ, in Hebrew--to help Jews leave the Soviet Union), to work among the Jews of the Soviet Union, I worked closely with representatives of the Joint, and knew some of them very well. At a meeting with one of them one day, I told the fellow how, as a boy of seven, I had met this "uncle" at the train station at the Latvian border. That fellow told me that in 1922 the Joint received Soviet permission to help those Jews who were war refugees. No doubt that the "uncle" was from the Joint. Then this Joint representative concluded, "Now this little boy of seven has grown and is an important source of information for us in everything concerning aiding Russian Jewry today."

To return to where I was--In Riga, we said goodbye to our dearly loved grandmother. I was very sad and probably cried. Mother explained that grandmother had not seen her daughters for many years and yearned for them.

Nechemia's grandmother on his father's side

After parting from grandmother, we continued by train to Tallinn. My childhood years, that had encompassed Ruyene, Perm and Petrograd were over and gone.

Tallinn, School and Youth Movement

Aunt Debora Gurevitz received us warmly and with joy. The aunt was married to a widower, a prosperous grain merchant. They welcomed us into their spacious apartment with open arms that first day. The family consisted of my aunt and her husband, their young son, and three older children of her husband's by his first marriage. Next to the apartment were the uncle's offices. I don't know who really worked in the office, as the uncle was not in good health and only went to the office from time to time. I think it may have been the eldest daughter that did most of the work there.

Aunt Debora was an educated woman of striking appearance, and she made great efforts to ease our adjustment to Tallinn. This was quite difficult, for although she had help for the care of the house, she had to look after the needs of her sick, weak husband. Her young son was also sickly and caring for both took much of her time. To me, she looked tired and drawn, but she always smiled at me and patted my head.

From the outset we felt a bit uncomfortable in the house. Despite the welcome, we felt that the uncle did not really like us, nor did his older children want this addition to their household. The house we lived in was in a swanky neighborhood on a central thoroughfare and we did not have any playing area nearby. In short, both I and my sister did not feel comfortable there. The uncle looked grouchy most of the time, so we kept mostly to our own room. My mother went out to look for work and did not have much time for us. She also looked worried and unhappy most of the time because she too felt that we were unwanted guests, despite all the sincere efforts of her sister.

I do not remember how long it took, but soon my mother found a small, modest apartment. We were overjoyed. Mother found work which was barely enough to support us. Sometimes, if we needed a little help, it was the friends that Mother made who came to our aid, more than our relatives. Some time later, Mother found a better job, so life was a bit easier. The Jewish community in Tallinn numbered more than two thousand people, and there were two Jewish Clubs. One--a club for Zionists and their supporters, called "The Bialik Club," and the other, "the Peretz Club." Both were social-cultural clubs. Jews would meet there for a cup of coffee or a game of cards or chess. In the Bialik Club there was a small lunch-counter, cafeteria which served lunches and suppers. My mother managed this; she also cooked and served. About ten people would come to have their meals there; most of them were Jewish businessmen visiting Tallinn. We received two small rooms from the club, in which we lived. Mother was very pleased with this arrangement. She could watch over us while doing her work.

The Chazan (Cantor) of the synagogue taught singing in the school. He chose me to participate in the synagogue choir. The choir consisted of about twenty children and a dozen men. Between holidays there would be rehearsals, and on holidays, we would sing with the cantor. The cantor was a nice person and I participated willingly in the choir, but that did not bring me closer to religion. Aside from the High Holidays, I don't think I ever went to the synagogue.

From term to term, I improved in my studies and by the time I finished elementary school, I was one of the outstanding pupils. During vacations, I spent most of my time with the other pupils that did not go to camp. We invented games that brought us to all corners of the city. Tallinn was a city that had a character of its own. It is a port on the Gulf of Finland that was established by Danish invaders, on the ruins of which the Estonian city of Lindnese was founded. Tallinn became its Estonian name. The Germans and Russians used the name Revel, that has its roots in the Danish word "Rock." Indeed, the city was first built on rocky outcrops and low hills. The Germans built the fortified center of the city on top of a hill called Domberg--"Church Hill" in German. This old section of Tallinn is built in Gothic style. The narrow streets and the old church are very well-preserved. The inhabitants of the Domberg keep the area in clean and excellent condition, and this lends a certain charm to the city. Around the Domberg section, parts of the old wall of the town are still standing, with round guard towers here and there, and gardens encircling them. In the spring and summer, I played there often. In the winter, after the snow had fallen, we would go tobogganing on the slopes of the gardens.

As a Gymnasium student, I would go for walks in the park with my school chums. We would walk along the main boulevard and remark on the beauty of the blonde Estonian girls that were passing by, and in winter we would go skiing.

I entered Secondary School (the Jewish Gymnasium) with a good deal of self-assurance, since I had done extremely well in elementary school. The Jewish Gymnasium was a recognized government secondary school. The young Estonian Republic was liberal, and not only the large minorities--Russian and German--had cultural autonomy, but even the small Jewish minority enjoyed all the privileges that the government granted. In Tallinn, with its 2200 Jews, and Tartu, with 900 Jews, the government built secondary schools, and in the University of Tartu there was a cathedra for the study of Jewish culture.

Even under the Empire, Estonia was noted for its high standard of education and culture. The percentage of literacy was much higher there than in the rest of Russia. The percentage of those attending high school and university was also much higher. Tartu University was one of the best in the Russian Empire. Little independent Estonia invested a great deal of its resources in education, art and culture. Among the cultural institutions in Tallinn, which was not a large city, there was an opera house and ballet, theaters, and a symphony orchestra.

Until quite recently, Estonia had remained outside the Pale of Settlement (the region of Russia where Jews were allowed to reside). Therefore, most of Estonia's Jews came from Latvia, Lithuania, or Poland.

the Tsar's Summer Palace in Tallinn

The Jewish community was segmented by a diversity of political leanings. The Jewish school in Tallinn found a partial solution for some of the problems. The language of study was Russian. Hebrew and Yiddish were taught, in addition to Estonian and German. Estonia was also outstanding in the field of sports education. The influence of Finland, the Northern neighbor, was felt in this aspect. Finland was a world-class competitor in many kinds of sports. Our school tried to keep up to the standard in this area also.

I recall this period of Gymnasium study with many pleasant memories. I liked the school very much and had respect for most of the teachers. I felt I had a good standing among my classmates and often helped other students in some subjects. This was quite important, and not so easy to achieve as most Jews of Tallinn were in the well-to-do merchant or professional class, and our family were poorer and not on the same social level of the "sons of the well-to-do." I was a special case, and despite the fact that my mother barely earned enough for our upkeep, I was rather popular with my classmates. Despite our poverty, my mother always sent us to school dressed neatly and cleanly and we participated in all the after-hours social events. When I think of what this stage in our lives meant for my sister and myself, I value very highly all that my dear mother did for us, in raising us under such difficult conditions so that we could feel secure and equal to our wealthier peers.

I owe a great deal to my high school teachers (most of them were not Jewish). The good ones broadened my horizons and gave me the will to learn and the knowledge of how to go about studying on my own by reading books. The lessons of the teacher of Russian literature were fascinating. The German language teacher gave us a love for the German classics, Schiller, Goethe and Heine. He was also our class director. In the spring he would take the class for hikes in the woods and this brought him to a good rapport with the students. I recall the day before the elections in Germany, he came into the class and said, "I hope Field Marshal Von Hindenburg will save us from that madman!" He devoted the whole of the following lesson to this topic. The math teacher was an engineer and a former Russian Army officer. He and the teacher of German had come to Tallinn from Peterburg. He was a strict and exacting teacher, but he knew how to interest us in the subject. The Yiddish teacher was a likable fellow and he was a Zionist also. The Director of the school was also the history teacher. I did not care for him as an individual, but I respected him as a teacher; he happened to be anti-Zionist. I recall some of his lessons to this very day.

The physics teacher was an old bore. I wasn't very good at learning Estonian. The teacher was a good-looking young woman. I paid more attention to her shapely legs than to what she was saying. The deep decollettage of her gowns also drew our attention. Two floors of the building of our school housed the Russian Gymnasium. Between lessons we would examine the Russian girls, also, but not much more than that. We would play basketball and volleyball against the Russian boys.

High School Photo - Nechemia is marked by an arrow

Outside the school, I led a full and active life. I was active in various fields of sport and had a busy social life. I played basketball and football (soccer) and volleyball. In the summer I was busy in field events and swimming. In winter I preferred skiing and ice skating. In some of these events I was an above-average player and competed for our school against other teams from Tallinn.

My social activity can be divided into two phases, the first--before the great change that affected me, and the second--that which came after that change. While still at school, I joined the "Jewish Battalion," this was part of the boy scout movement. I was a scout for some length of time, until after I went to the gymnasium. I liked the activity of the scouts and nature, hikes and camping in the woods, discussions and singing around the campfire,and erecting towers in the forest (without nails, using rope only). When I was 15 years old, I was drafted into the Zionist student club, "Emuna" (Faith). This club tried to resemble all the other clubs of the time. Students continued on into university into other Jewish student clubs in the University of Tartu. One such club was called "Hasmonia" (Russian for Hashmonaim). The other club was called "Limovia." These two clubs, like all the other Russian and German clubs, called themselves "societies," and each had a flag and a theme song, in addition to the student anthem, "Gaudeamos Igitur" which was sung in Latin. The Society had a strict code of behavior, the older boys held power over the "rookies" and the chief of the Society was all-powerful. The Tartu "societies" were run according to the German style, and they trained in dueling. I heard of actual duels that took place and the participants were wounded. I did not see any students with scars on their faces in Estonia, but I heard this was quite a common occurrence in Germany. Each Society had a clubhouse in which the students spent their spare time. The older students broke in the younger ones to beer drinking. They would also meet in the pubs in town and drink beer and sing. One could tell to which Society a student belonged by the color of his hat.

Of the two "societies" Limovia was more severe in the formalities of the anthem and other accoutrements of the Society and was also apolitical; it belonged to no specific party or cultural element. Hasmonia, on the other hand, was less formal as a Society, but defined itself as Zionist. Actually, most members of Hasmonia were connected to the Revisionist branch of the Zionist Movement.

I have described all of this in some detail because all of us who were members of Emuna saw ourselves as potential members of Hasmonia, even if we were not Revisionists, because we preferred a Zionist affiliation to that of the assimilationists.

I don't remember exactly how the Emuna Society chose its new members, but I do recall that not every candidate was accepted. During the first semester we learned the rules and regulations of the Society, we learned something about the Land of Israel and some of the fundamentals of what Zionism was. When we were accepted into the Society, we met at least once a week in the small club room decorated with the flag of the Society, with pictures of Herzl and Max Nordau and classes of alumni of the Society. At the meetings, having finished with the conduct of the internal affairs, there would be lectures and discussions. The lectures usually dealt with chapters in the History of the Jewish People (following the book on this subject by Simon Dubnow), and on the development of the Zionist Movement. The latter also dealt with actual, current problems of Zionism. Most of the lectures were prepared by members of the Society.

Perhaps the older members of the Society were impressed with my lectures because while still rather young, I was chosen as chairman of the Society. I found this highly complimentary that the members of my class expressed their trust in me in such a way and I was congratulated by many.

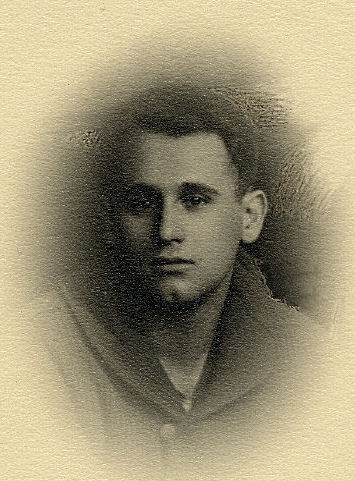

Nechemia, Chairman of Emuna Society

The story of "the great change" starts in my next-to-last term. Most of the fellows in the Emuna group to which I belonged were from rather wealthy families. From that point of view I was an outsider, and I must have felt so. I already wrote that I had no love for the Revisionism of Jabotinsky. I already knew something of Ben-Gurion and the labor movement in Israel. I had heard a lecture by Yosef Beretz, one of the founders of Dagania, who visited Tallinn on behalf of the Jewish National Fund and Keren Hayesod ; it seems that I was ripe for a change. One day, a striking young man arrived in Tallinn, dressed in a brown jacket, a gray shirt, riding breeches and high shoes with knee-high stockings. I was told that this was not a uniform but the ordinary dress of the older level of "Shomrim"--that is, the Hashomer Hatzair Youth Movement, pioneer youth scouts in Latvia. The name of this interesting fellow was Lasik Goldberg. Lasik lived and was educated in the provincial town of Rezekna and in the youth movemet "Netzach" (Noar Tzioni Chalutzi--Pioneer Zionist Youth). He was sent by his movement for the express purpose of building branches of the Netzach movement in Estonia. I learned all this from my first conversation with Lasik. The meeting originated through a member of the Socialist Zionist movement in Tallinn who was a distant relative of mine and recommended me to Lasik.

Lasik Goldberg

I was in turmoil. I lost interest in my activities in other frameworks and saw them as unimportant, a waste of time. My activity in Emuna and Hasmonia ceased and I lost all interest and contact with them. I devoted myself completely to the task that Lasik had given me; I was to convince the students in our Jewish school to join our new movement which Lasik was organizing. I suggested to Lasik that we organize the class of 14-15-year-olds, as I did not see any appropriate candidates in my own class. The wealthy students in my class were nice but too comfortable with their surroundings to be attracted to the movement.

I must have found the right road to the hearts and minds of the younger children. Lasik himself worked to get the support of parents for the new movement, which he thought should be within the framework of the scout movement. We resurrected the Jewish contingent of the Boy Scouts with the accompanying uniform and flag, etc. We had a blue/white Jewish flag with the Boy Scout symbol in the middle. One of the boys learned to play the drum and became very good at it. Lasik took my advice and we started with one group of kids from 10-12 and another group from 12-16. We figured that the youngsters would mature into the older levels of the movement. We soon had quite a few groups of children organized into units. The unit that I myself lead was called "Trumpledor," but I also met and helped the leaders of the other younger groups.

Among the Netzach leaders in Tallinn

Education in the movement predicated personal example on the part of the leader. I tried to be the perfect scout, and since I loved scouting, that was not too difficult for me. I was swallowed up by the movement and my marks in school suffered. However, I passed my exams well.

My sister went to study in Tartu and married another student who had almost completed his studies (he belonged to Limovia). I remained with Mother, to whom I did not devote enough time, but she never complained. She encouraged me to continue on the path I had chosen. My mother rented two rooms to the movement and these were our first Moadon (meeting place) in Tallinn. This was convenient for all, as I was active, and also close to home.

Lena, Nechemia's sister

I was 17-years-old at that time and had some doubts as to my abilities. Two 20-year-old fellows met me at the pier and we made each other's acquaintance. They were the leaders of the Jewish Scouts in Helsinki. From the port they took me to my dwelling place that they had prepared for me, not far from the center of the city, next to the synagogue. It was quite a comfortable room, and was usually used to house the Darshanim (those that were invited to lecture to the congregation on Saturdays). These were rabbis or scholars that came from Latvia or Lithuania.

I left my luggage in the room and we went to the home of one of the fellows to eat supper. After supper we spent several hours in conversation. They told me of the difficulties of parents in a small community with not very many children. The community is interested in the children doing scout work, but they would prefer it to have a Jewish flavor. They told me what they expected of me and I told them what I had prepared to do. We decided to meet again, they gave me some pocket money and said that until Pesach I would eat at the houses of parents of the children. When I got back to my room I counted the money and realized I had really been given very very little pocket money. There must have been some mix-up. Lasik thought they would cover all my expenses, and they thought that Lasik would cover them. I wrote to Tallinn and told them to send me more money, and meanwhile I had to nurture every coin.

I had my first meetings with the scouts and I was encouraged by them. The parents knew Yiddish very well, but the children understood with some difficulty. However, we overcame that and in general, they listened with interest to what I had to say and there was a good atmosphere at the meetings. Together with the other leaders we made plans for the Pesach holiday which was soon to begin. Before the holiday vacation started, I had some free time in the mornings, so I made myself familiar with Helsinki and toured the museums.

I ran out of money and when it came to the Seder night I was starved, as I hadn't eaten all day. I remember that Seder to this day. Two families were seated at one table, including children and grandchildren. The table was prepared in the tradition of the Seder and everything was there in abundance. The Seder was conducted by a distinguished-looking gentleman with a pleasant voice. We read the whole Haggada and heard explicit explanations. I thought it would never end. When we finally started eating, I tried everything there was to eat and in quantity. By the time we reached the Had Gadya (a song near the conclusion of the Seder) I had eaten my fill, I was in a good mood and sang lustily. I had been redeemed.

During the Pesach holidays I conducted many activities; I was full of energy. I felt I was doing my job well and that the children were enjoying themselves. Aside from activities in the clubroom, we also went out to the forests around the city and we spent nights camped in tents. It was nice to hear the children singing Hebrew songs around the campfire (probably for the first time in their lives). I liked the Finnish scenery, the dark green of the tall pine trees, the gray outcroppings of rock on the shores of many lakes.

Now time started to fly. I managed to visit the city of Turko, far to the west of Helsinki. There was a very small community of Jews there, and they seemed very isolated. However, their determination to hold on to their Jewish identity amazed me. I gathered together the dozen or so children and talked to them and to their parents.

Upon returning to Helsinki I made plans for finishing up my shlichut. I had talks with the younger and older leaders and made plans for the following summer and winter holidays. They made me a little farewell party and so, with a feeling both of satisfaction and of sadness, my first shlichut came to and end. I thought I had accomplished quite a bit in a short time, but had the feeling that without a continuation, it could not last for long. I did not think I would ever return to Finland, but I was wrong. Twenty years elapsed before I returned, but this time it was an altogether different kind of mission. (I described that mission in my book "Code Name: Nativ" {Path}). I remember my first visit in detail.

I returned to Tallinn and divided my time between my final year studies in Gymnasium and my activity in the movement. I had to prepare for my final exams in school. At this moment I had to make a very difficult decision. This was the situation: There were thousands of Chalutzim (Pioneers) in central and eastern Europe, many of whom wanted to make Aliya (immigrate) to Palestine, but could not get certificates because of the limits on immigration imposed by the British Government. Some of them went to villages to work in agriculture, in groups called Hachsharot (Training Farms). Others, as they grew older, became adult sympathizers fo the Zionist Movement. Lasik wanted to go back to Latvia to prepare himself for Aliya and he wanted me to replace him as the leader of the Movement in Estonia. However, a group also formed in Estonia to go on Hachshara, and as I was one of the oldest, I wanted to join them, according to the principle of "self-realization" (or self-fulfillment; in Hebrew, Hagshama Atzmit). Of course this meant leaving my mother all alone, but she was very supportive and urged me to do what was best for me. Since our group had to be at the farmer's village for the hay harvest, we would have to leave the city before graduation ceremony. Mother said she would take my diploma and bring it to me on her first visit.

In the spring,we set out to a large farm far from Tallinn, in western Estonia.

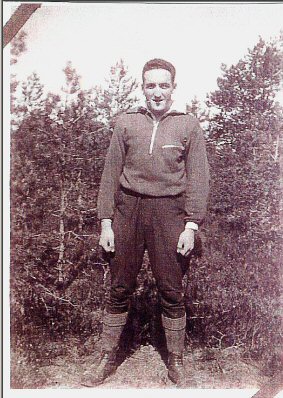

the Hachshara group

The regular workers did the jobs requiring greater skill, plowing, sowing, harvesting and working with the horses. We did the simple seasonal work, harvesting with scythes, stacking and loading hay with pitchforks, removing manure from the barn and spreading it in the fields. We also cleared fields of stones. The work was very hard and the days were very long. We did our best not to fall behind the husky, experienced village women, but we didn't always succeed. I grew blisters on my hands and my back ached terribly. By the evening, I would get back to the attic exhausted and throw myself on my bed of straw. Only after several weeks of "black labor" we started doing more skilled work. Some of us were even allowed to drive the horses.

At first, we were too tired after the day's work to do anything in the evenings. It took us about one month to become accustomed to physical labor. When the blisters healed and the fatigue lessened, we would stay awake longer and talk or sometimes go for evening walks. As I look back at that period, I recall that the sure sign that we had stood the test of manual labor was when we would stay up till late at night singing. We sang songs of the Land of Israel and we sang Hassidic Nigunim (melodies). Far, far away from the Land of Israel, by the shores of the Baltic Sea, we sang, "Ve Ulai lo hayu hadvarim le olam Ve ulai..." (a very popular song by the poetess Rachel, about the Sea of Galilee). We were not troubled by the fact that nearby were the cold gray waters of the Baltic; we were dreaming, probably.

We asked our relatives not to visit us until we had settled in. My mother arrived in the latter half of the summer. I thought she would be troubled by my appearance, but she was true to form; she said, "You look tanned and healthy, and a bit slimmer." I showed her my hands, the hands of a farmhand, and I told her that the blisters had hardened and did not trouble me. We went for a walk in the fields and she told me a little about herself and my sister. I told her frankly how difficult the first days were until we got used to the work. It was a great day for both of us.

Autumn had almost arrived and we received a letter from Lasik that he had rented a small house for our group to live in, in a workers' section on the outskirts of Tallinn. He also mentioned the possibility that some of the group might get certificates for immigration to Palestine.

The day of departure finally arrived, and we took leave of the fat little German and the steady workers. We were the last of the temporary workers to go. We had had some very difficult times there, but also some very beautiful experiences.

We returned to Tallinn and I went to tell my mother that I would be living with the rest of the group, but would come to see her often. Mother was still living in the apartment where she had rented a room to the movement. I was to take over from Lasik in the movement for half the time, and the other half, I was at the service of our group. The house we lived in was very crowded, but there was a friendly atmosphere there. Several months after our having moved there several chaverim (friends, members) received certificates of immigration to Palestine. They left, and new memebers came to join us in their stead.

The movement meetings were in the room in my mother's house, so I would see her before and after the meetings and we would have long conversations. I loved discussing things with my mother. She was a sympathetic listener and we understood each other very well. One day I came up to her room and it was locked. Someone told me she had gone to the hospital, so I ran there. I stood by her bedside shocked; she was very pale and talked without raising her head from the pillow. "Don't worry and don't be sad, everything will be okay," she said. I kissed her forehead. Several days later I stood by her grave and read Kaddish (the prayer for the dead) with tears in my eyes and my heart.

I returned to the kibbutz apartment (commune) and lay on my bed. One by one, chaverim and chaverot (friends, male and female) came in and sat around. No one spoke; they were just there with me for a long time...

It was then time to say goodbye to Lasik. We not only respected him as our leader, we loved him as an individual. He took me to Latvia to participate in several events there and to get more of a feel for the movement, and I was impressed. It was not simple to "fill his boots" and only after I felt that I had made some headway in the movement did I gain more confidence.

Most of my time was taken up with the Legion of the movement in Tallinn, but I also would visit the other branches (four smaller ones) in the other cities of Estonia, and sometimes the leaders of those branches came to see me. Most of the mail and other printed educational material was distributed to all of us direct from Riga.

The group in Tallinn grew. The best of the youth in the Jewish school came to us. We had a large group, with new leaders who worked together closely and were also good friends. The youth had a feeling they were doing something constructive and important. They liked the movement and they liked to spend time together in the Moadon (clubhouse). They enjoyed scouting and hiking and comping out, summer and winter. All these activities created close ties between the madrichim (leaders), as well as between them and the youth they were leading.

Head of the Tallinn Legion

The atmosphere of this camp was very good and I was proud of the behavior and achievements of my bunch. I recall a small passing incident: in the movement we usually did not encourage "romantic episodes" and there was comparatively little loose sexual interplay, and I also was wary of spoiling my reputation with the younger scouts by engaging in too loose behavior in this manner. But one day I happened to notice a beautiful, vivacious young woman in a group of scouts from Dvinsk. I was stricken with her and indirectly inquired about her and found out that her name was Beba Levin.

Beba Levin

Soon after this camp had closed down, there were some drastic changes in the Republic of Latvia. The Social-Democratic Party that had been in power was badly defeated by the right-wing conservative National Agrarian Party. The regime of their leader, Ulmanis was a domineering man who ruled almost single-handledly. There was no room for a socialist youth movement under his rule. With the aid of a member of Parliament, Rabbi Nurock, the government did allow the establishment of a youth movement going by the name of "Olim" (immigrants), the aim of which was to educate Jewish youth to immigrate to the Land of Israel.

The Netzach movement continued to operate, but did not hold any public meetings of any sort that would attract attention. The head committee of Netzach therefore decided to hold a leadership seminar in Estonia and I was to make all the arrangements for this activity. The seminar was a success and it was also there that I met for the first time a promising young leader, Rivka Dukravitz. She was from Dvinsk and appeared to be a serious and capable person. This first perception did not alter even after many years of living in the same kibbutz, Kfar Blum.

As the summer approached, I was asked by the movement leadership committee to find a place to hold the summer camp for the Latvian movement in Estonia, and to get the necessary tents and equipment and food supplies to run the camp for its duration. I found what looked to be the most suitable place on the island of Serema, not far from the mainland of southern Estonia. The Latvians came by ship from Latvia and we came via a port in Estonia to the south side of this island, somewhat inland from the main town of Kuresare, and hidden in the woods with only some farmers' houses spread about, and the small fields they cultivated. We bought our food in the town, and some from the surrounding farmers. We drew water from the well in buckets. It was a wonderful camp and a uniting experience which gave added strength and vigor to the movement.

Kuresare Summer Camp staff, 1935

This camp was my last activity in Estonia. I was told to find someone to take my place in Tallinn and I was called to join the group of leaders in Riga, where the movement numbered about 300 members of all ages. I had started preparing someone to take over from me, because I thought the time was approaching for me to make Aliya (immigrate to Palestine). I chose Monka Shmotkin as being the most capable and responsible, even if sometimes a bit bombastic. There was a group of other good people as leaders of the movement. I was certain that they would get along without me. More than fifty years have gone by since I took my leave of the movement in Tallinn.

In 1990 I visited the city again, with Beba. I found that besides the few who had managed to emigrate to Israel, very few others remained alive. I learned that when the German Army drew close, the group of leaders, with Monka at their head, decided that at that moment the most important matter was the fight against the Nazis, so they volunteered to join a battalion of Estonian-Soviet soldiers and fell in the course of battle. We sat in the house of Vulia Shatz' sister with those that remained and recalled the "good old days." We were warmly received by them and I was very moved by the memories, but deeply saddened. I'll go back to the past later.

Riga, A Mission for the Movement, Aliya

I took my leave of my sister and the kids I worked with in the movement and the leaders of the Socialist-Zionist Party that had supported our work. I arrived in Riga, where they had prepared two jobs for me: I was to be in charge of all the scouts on one level (age group) and specifically, I was to lead the Herzlia troop. I considered the latter to be the more important, because if I succeeded with that one group it would have a positive repercussion on the whole age level. When I left for Riga I knew that all the madrichim (leaders) who did not have a home in the city had to live very frugally, because the sum that the movement was able to give them for their support was a pittance. This did not worry me particularly, however, as even in Tallinn I had learned to live on very little money. In Riga I boarded for a time with Eliezer Porat (Fried, at that time). He came from a small town in the hinterland to study at a technical school in Riga. This had a good side to it since he often received packages from home and he would share them with me. During the subsequent years that I lived in Riga, I wandered from one little hole of a room to another, all over the city, but as I said, these difficulties did not particularly bother me.

The head of the Riga Legion was Chanan Feldman (Shadmi). He took charge mostly of the older group of members, called Shomrim (guards). Chanan (generally called by his nickname, Chodgik) was the supposed "culture expert" of the movement; he knew Hebrew very well, and knew all that was going on in the Zionist world and in Palestine. I had the impression that he was very well-respected in the movement. I got acquainted with the Central Committee of the movement and with the Shlichim (emissaries) from Palestine. I knew they were all waiting to see how this promising young fellow would make out. I realized that I had to prove myself at my job in these new surroundings.

My first meeting with the Herzlia troop went off very well and I gained much confidence. This was a big group of about 40 boys and girls; they were lively and intelligent, full of life and a bit noisy. Definitely to my liking. I felt, of course, that they were also testing me, to see what sort of a character was that Estonian that they had been saddled with.

I was warned that it would not be easy to work with this group, as the one who preceded me, Yisrulik Astrachan, had been very popular and very well liked by the group. However, from the outset, I felt at ease with them. About a third of the group came from the wealthier areas of the city, and the rest came mostly from the poorer quarter, "Moskva" which they called "Moskatch." Many of those from this quarter did not have more than elementary education, but others were going to Hebrew gymnasium. It was obvious that if I wanted to succeed, I would have to bridge between the two halves of the group, with their differing economic and cultural backgrounds. My plan was to be a disciplinarian when it came to formal meetings and other activities, but on an individual and social level, to be as kind and understanding as possible. When we would gather before the meetings at the moadon they would "latch on" to me and badger me with all sorts of provocative questions, and kid around with me; but once the meetings got going, I was the leader and took charge.

Once the meeting was over, we would leave together and walk for quite a long way until our roads parted. On these walks, I would act as "one of the gang" and we would talk about anything that entered our heads, but I also found ways to tell them a bit about myself and the movement in Tallinn. I found the kids from Moskatch particularly interesting and noted that what they lacked in formal education, they made up for in their knowledge of the ways of the world. The closer I came to any of the children, the more I could feel their inner world, so that in truth, I felt very close to the whole group and they bared more of their thoughts and feelings to me.

I did not only have activities in the moadon, but as in Tallinn, we went on many hikes and camped out in the woods. The troop flourished and more boys and girls from all over the city joined, and the name and reputation of the troop grew. My success with the Herzlia troop helped me with the whole age group, of course. I started preparing the troop for the transfer to the next age level. Along with an intensification of lectures, etc., I continued with the scouting and camping, and I tried to find new ways to do things we had previously done. Even hikes and camps can become monotonous. Once, I even went a bit too far, I'm afraid, as I look back on one incident. Through the help of one of the boys we were able to procure a pretty large launch, which we used to cross the Bay of Riga, and camp at a beautiful spot on the far side of the shore. On the way back, when we were still about a kilometer from shore, the motor went dead. I decided to swim to shore to get help, and one of the boys whom I knew to be a very good swimmer came with me. We swam to shore and managed to get someone to tow our launch back in, and so we arrived back in Riga safe and sound that evening; but the adventure could have ended badly.

It seems that some of the boys and girls in the troop had good enough relations with their parents so that they could tell them of the various activities in the troop. As a result, I became known to them as the "meshugener Est," the crazy Estonian. The kids in the troop liked that, and it served to improve my standing with them. I was convinced that the sum of these activities was not only good for the troop, but also strengthened the boys and girls as individuals.

The Herzlia troop leader

While working in Riga, I had the good fortune to participate in a very important and impressive convention of the whole European movement, which was organized by the shlichim (emissaries) from Palestine. There were groups from the Netzach movement in Europe or other groups close to Netzach under other names, such as Habonim from England and Blau Weiss from Austria. There were also groups from Czechoslovakia, Austria, Transylvania, Yugoslavia, England, Latvia and Lithuania. Years later, they all became Habonim. This was an interesting meeting of Jewish youth from varying cultures who believed in similar ideals. Many of the lectures were by the shlichim from Israel, amongst whom I recall Elik Shomroni from Afikim especially, and Lasia Galili, also from Afikim. But to my mind, the central and most impressive character at the convention was Berl Katznelson, the well-known leader of the Labor Party in Palestine. He was a short man with graying curly hair and penetrating, intelligent eyes. He fascinated us and I recall that he did not dwell so much on the problems of the Labor Party in Palestine, but more about the problems of maturing Jewish youth in the Diaspora. During the question and answer session, he was asked about boy-girl relationships and he replied that it is true that young people do have trouble finding solutions for their sexual relationships, but then even adults, and he, too, didn't have all the answers.

I was very pleased with my Latvian Herzlia group at the convention. For example, before we left Riga, I suggested that we visit Vienna and Warsaw on the way to the convention, and Prague on the way back. In order to meet the expenses, they themselves decided to make a common "kitty" into which each would put all that they could get from home, and then share all expenses from the kitty. This example was followed by all the others in the Latvian contingent.

I recall my years of work with the Herzlia troop as one of the best periods in my life. I liked the whole gang very much and remember them vividly. Dicky, the fat gymnast, clever and responsible; Leibele, the strong man from the Moskatch quarter, that even the goy hooligans were afraid of; Tomachik, with a great sense of humor, fair and practical, whose older sister was already in Palestine and a member of Kfar Giladi. Cute, curly-haired Breindl was also from Moskatch; she was diligent in everything she did. Mulka and Yaka were the best of friends but totally different. Mulka was tall, strong and athletic,with a strong personality. Yaka was frail and blond, a good pianist, but did not shirk from hard work. Hemi was a sensitive boy; Feigele was good-hearted; Mulka Levin looked like a little boy but his mind was razor sharp. And there were others. All in all, a great gang.

Once again I will detour from my story and return to it shortly: there were difficult years for the Jews of Latvia after I had made Aliya (immigrated to Eretz Yisrael). With the outbreak of WWII, Latvia was overcome by Soviet Russia (as was arranged in a pact with Nazi Germany). This was a difficult period for the Jews there, but it did not last long. The Germans attacked the Russians, invaded the Baltic countries and drew near Latvia. The Jews fled into Eastern Russia and those that did not leave in time were exterminated in the Holocaust.

Some of my Herzlia scouts managed to get to Palestine before the outbreak of the war, but a greater number found themselves far from Latvia in eastern Russia or central Asia. I myself came to Palestine a year and a half before the outbreak of the war. We in Palestine knew very little about the fate of our brothers in the Baltic countries until after the war was over.

Along with all the Jews who had gone east were a good number of members of Netzach. They tried to keep in contact with each other and succeeded in time in contacting a good many in several central locations in the Asiatic Republics of the Soviet Union. When the war was over, they started to look for ways to leave the boundaries of the Soviet Union and make Aliya to Palestine. The border of Poland seemed the most likely place to cross and, inded, in the beginning, their efforts were successful. In time, contact was made with the Israeli members of the Bricha (young men sent specially from Israel to help Jews read the Mediterranean ports, or soldiers of the Jewish Brigade, ordered by the Jewish Underground to do this job). Mulka and Yaka were among those organizing these border crossings. They needed more money to do their work, and Mulka crossed over to Italy and met shlichim from Israel there and asked them for help. When he was asked to prove who he said he was, he gave them my name. I was excited and thrilled to hear of him, and begged the shlichim to do all they could for him. He received the money and the brave fellow went back to the Polish border to continue his work. As happens in this sort of activity, the Soviet authorities caught on to the scheme, and all those involved were arrested. Mulka and Yaka found themselves in a prison camp. Mulka, the strong one, took sick and died in the camp. Yaka, the weaker one physically, managed to survive and after several years, finally managed to reach Israel, via Poland.

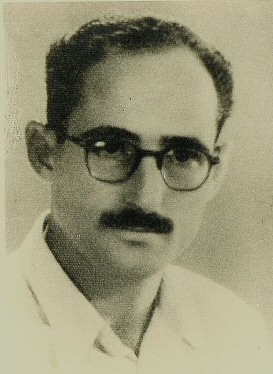

Yaka worked with me for years in "Nativ" (path, route--underground Jewish organization for aiding Soviet Jewry to reach Israel). With a combination of ability and thoroughness, he collected information on the state of Eastern European Jewry, and the struggle of those active in Aliya from the Soviet Union. He also aided those who worked for Nativ in the West, who tried to gain support from people and governments to raise money for the work in the east, or to help "open the gates" of the eastern countries so that the Jews would be able to leave. There was also the work of trying to free those Jews that had been incarcerated in prison camps for the offense of being Zionists. He played a role in improving the radio programs that were beamed at the Eastern European countries. At a rather early age, he suffered from heart disease, and this is what brought him down finally. In his last year, he published a book about his friend Mulka, who had been the most instrumental figure in the "stealing the Polish border" operation. The book was published shortly before Yaka passed away. More than once, Yaka and I would reminisce about the old days of the Herzlia troop. He once made an accounting and found that about twenty members of the group had reached Israel. Now I'll return to where I left off...

Mulka Levin

Even before we left for the camp in Czechoslovakia, I had been chosen to head the Legion of Riga, the biggest one in the Latvian mevement. I hope that did not cause my ego to swell too large. I now had more contact with the heads of the movement in Latvia, but except for Chanan, I never really formed really close ties with most of them, and that includes Rafael Bash, the leading figure in the Latvian movement, and I remained a sort of outsider.

Netzach Movement leaders, August, 1936

In my new job, I got to know the various Kibbutzei Hachshara (training groups waiting to make Aliya). Until this time, I had only visited one of them, and that was an agricultural training farm several tens of kilometers from Riga. I had brought the Herzlia troop to visit this place. We were very impressed to see young men and women doing all kinds of farm work; they worked with horses, plowed fields, milked cows, and spread straw and cleaned out manure. During the harvest, they did all the harvest work, etc. Among these new farmers, I met Moshe Nir, Chaya Nir, Yamima Ribeck and .. Beba Levin (do you remember her, the good-looking girl at the camp near Riga?).

This farm was the only one there was in Latvia for agricultural training. Most of the adult members of the movement who were waiting to make Aliya were living in apartments in cities all over the country, and they worked in the cities as laborers in order to earn their living. Those that had done hard physical labor before they went to the agricultural training farm found it easier to get used to the conditions there. For those who came straight from high school to the training farm, it was a much more difficult task. The conditions in the collective houses were also difficult; the food not like in their mama's home. However, were it not for their collective spirit and their movement background, it would have been next to impossible to hold out and make a go of it.

What depressed the chaverim most were the periods when there was no Aliya, or very little. At times, the mandatory power would limit immigration even more than usual, and certificates for making Aliya were rare. This would cause an extended stay for the veterans sharing their apartments, which led to complications of all kinds, especially as they did not know when this situation would end. On the other hand, when a good number of certificates arrived, there would be jubilation and a lifting of spirits.

Time flew by, and six years after I had entered the movement in Tallinn, my turn came to make Aliya. I received some money in order to buy clothes. I visited my sister and friends in Tallinn, and set out on an indirect trip to Palestine. Indirect, because the leaders of the movement who had met me in Vienna wanted me to stop over there and work for a time in the movement. Vienna was one of the most important centers of activity and thought in Europe between the two World Wars. It had been governed until recently by a militant Social-Democratic Party, supported by a strong labor union, but was now in the hands of reactionary elements who, in the end, negotiated the transfer of Austria to Nazi Germany. Shortly before I arrived there, the power was in the hands of the little dictator Dolfuss. It was said of his regime, "Dictatorship mellowed by inefficiency and diluted with Viennese light-headedness."

The character of the movement in Vienna was different than that of Latvia. Ideological and intellectual discussions were the main interest of the older level of the movement, and even of the younger levels. I felt there was too much talk. When I said that to the leaders, they said that is why they wanted me there.

I lived in a very nice section of Vienna with a very kind Zionist family. The Freulich family, who were adult members of the movement, did not lose much time and made Aliya, one following the other. The oldest son settled in Ein Gev, his younger brother also was there for a time but later moved on to Tel Aviv and was a successful theater director (he took the Hebrew name of Ronen). I enjoyed staying with them while in Vienna. At the same time, I put a lot of energy into the movement in Vienna, and in the forests on the hills above the city. Time passed quickly and then one day, I boarded the train for Trieste on the shore of the Adriatic, where I was booked on a ship to Haifa.

Beautiful Vienna, rich in its cultural and artistic institutions, was then only months away from Anschluss with Nazi Germany, but very many of the 200,000 Jews who lived there did not see the approaching danger. Many thought that Schushnig would make some convenient arrangement with Hitler.

On the train I had a lot of time to think. The farther we travelled, the more the past receded from memory. From early youth, trains have taken me from one known station of life to an unknown station. On this train to Trieste, I did not think of those stations behind me, but of the one before me, my future. I tried to imagine what was held in store for me. I knew that I was scheduled to join a Garin Hachshara (nucleus for establishing a new kibbutz), which was to gather at Kibbutz Afikim. This kibbutz, which was established by Russian members of the movement,was considered its crowning achievement. I was glad to start my life in Israel there.

When it came to boarding the ship, I was very affected and close to euphoria. What I felt at the time was probably a feeling which many young members of the movement had. I was 23, not a boy. I knew quite a bit about what was transpiring in Israel. I knew that not all was rosy in the Yishuv (Jewish settlement in Palestine), nor in the workers' movement, nor in the agricultural settlements. I knew there were difficulties in the process of absorbing people in the kibbutzim, and of people leaving the kibbutzim who had been active leaders in the movement. I had heard, but I wasn't worried and wasn't afraid of what was waiting for me in Palestine.

While writing these lines, I recall that we used to complain to the shlichim that they paint too rosy a picture of what goes on in Palestine, and didn't prepare us for the difficulties to be faced. One of them responded, "You hear only what you want to hear; you are deaf to the criticisms we make!" Now, as I recall it, he was correct. In any case, there I stood on the deck of the ship, enthusiastic and optimistic.

On the ship, I met two pairs of Olim (immigrants) who were members of our movement from Yugoslavia. I don't know how we recognized each other, as were were not dressed that differently from others, but still there is something about youth movement members that identifies them and causes them to recognize one another. Meir and Rivka Polikan and Tova and Yitzhak Levinger were planning to join other Yugoslavian immigrants that had been absorbed into Afikim. I mention them because several years later, Meir and Rivka joined the Anglo-Baltic kibbutz of which I was one of the founders. Tova Levinger was the older sister of Miriam Shalev, who made Aliya later and joined our kibbutz in Benyamina. I didn't ask the two Yugoslav couples how they felt, but I had the impression they were somewhat tense. I was full of curiosity and confidence when I disembarked from the ship in Haifa and took my first steps on the soil of the Land of Israel.

I was taken from the port, along with my Yugoslavian friends, to the absorption center at Bat-Galim, a suburb of Haifa. We were kept there until we had a medical check-up and received several vaccinations. Even this did not dampen my spirits. That is where Elik Shomroni found us and came to take us with him to Afikim. Elik told me that he knew the Yugoslavs wanted to settle in Afikim, but he had the feeling that I preferred to go to Ein Gev, a younger kibbutz on the eastern shore of Yam Kinneret (the Sea of Galilee). Elik was right; that is what I wanted. "How many members of the Garin have already arrived at Afikim?" was my first question.

To my mind, the road from Haifa to Afikim was a dream. It was the winter season and the fields and hills were a vivid green. As our luck would have it, it was a sunny winter day. I have since traveled from Haifa to Tiberias and Afikim dozens of times, but I remember this first time, along with Elik's explanations, as if it were yesterday. Once we left Haifa behind, we came to Yagur, the biggest kibbutz at that time, then we passed Sheikh Abreik (home of one of the first Shomrim {guards} in the Valley of Jezreel), in the direction of Nazareth. From the hills we could see the breadth of the Jezreel Valley. We passed through Nazareth, the biggest Arab town in the region, with its old churches, and headed for Tiberias. When we were not far from Tiberias, Elik, who had been explaining non-stop, said that soon the Kinneret would come into view. All the journey I had been astounded by the scenery, but when the view of the Kinneret hit my eyes, it was something special, extraordinary. In the movment, we had read of the Kinneret and sung of the Kinneret and dreamt of the Kinneret. The view before us was fantastic in its beauty. The deep blue of the water below, with the wall of the Golan Heights behind it and Tiberias hugging the shore near us, and one could see the road twisting down the slope towards the town.

Old Tiberias, with its old buildings of grey-black stone, also made an impression on us. We continued south along the lake, passing the Moshava (village) Kinneret. Then followed Kvutzat Kinneret. We crossed over the Jordan River on the bridge close to where the Jordan leaves the Kinneret. All this was completely new to me, but somehow I seemed to feel that I recognized it. A short distance before Tzemach, which was then an unfriendly Arab town, the road turned south and traveled along the length of the valley. Parallel to the road ran the "Emek Railway" (from Tzemach to Haifa). On both sides of the road grew the bright green fields of alfalfa and clover, stands of banana trees and grapefruit orchards. In the middle of the valley, we turned right into Afikim, my first stop in the Land of Israel.